DOI: 10.14714/CP101.1807

© by the author(s). This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0.

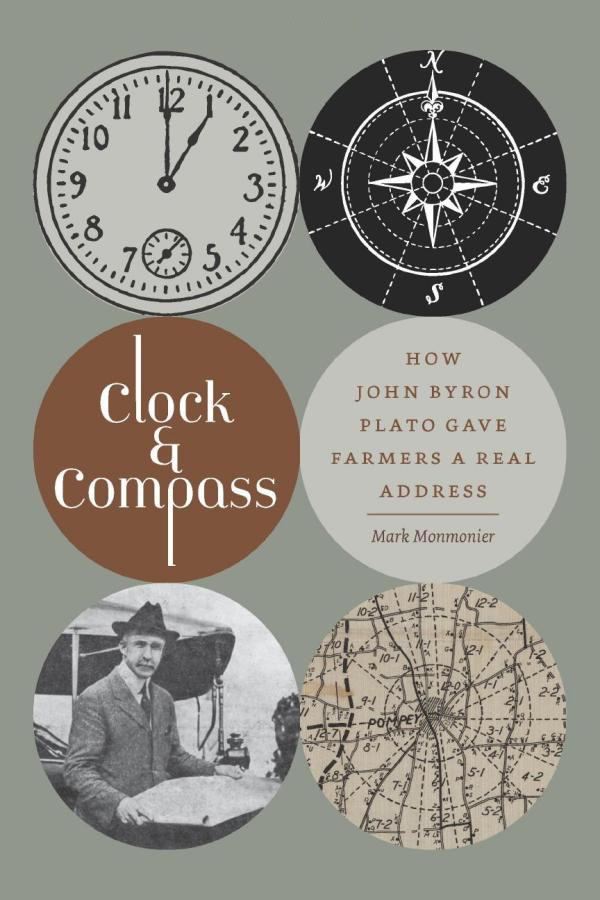

Review of Clock and Compass: How John Byron Plato Gave Farmers a Real Address

REVIEW 1 OF 2 FOR THIS TITLE

By Mark Monmonier

University of Iowa Press, 2022

181 pages

Paperback: $19.95, ISBN 978-1-60938-821-8

Review by: Russell S. Kirby, University of South Florida (he/him)

The scholarly practice of contributing books and monographs to the literature has deep roots in the culture of academia, but relatively few professors author books nowadays. Mark Monmonier is a notable exception, a professor of geography and cartography who has written twenty books that, both individually and collectively, have shaped the way we think about maps, their uses, and their abuses, as well as their meanings in the world of business, international politics, and our everyday life. While some of his books focus on issues central to the discipline of cartography, such as How to Lie with Maps (1991) and Mapping It Out (1993), Monmonier’s more recent work deals with narrower topics, including, among others: how maps are used in the news media and weather reporting, and on the origins of place names.

In Clock and Compass, Monmonier delves into an aspect of American cartographic history that was given brief mention in his previous book on Patents and Cartographic Inventions (2017), but has otherwise been a historical footnote. Faced with the challenge of how to give farmers and rural residents identifiable addresses in the early twentieth century, and presumably also looking for a path to his economic livelihood, John Byron Plato developed and patented a scheme that he called the Clock System to identify locations based on direction (as hours on a clock face) and straight line distance from a market town center. Plato proceeded to market his invention to local citizens, using advertising on printed Clock System maps to generate income. His business endeavors lacked the major investment necessary to become statewide or national, although other entrepreneurs continued to market county maps based on the clock (and the related compass) idea into the 1940s.

Monmonier’s book consists of ten relatively short chapters, the first of which sets the stage while the last seeks to place the topic of Plato’s Clock System in perspective. In between, Plato’s life and entrepreneurial career are chronicled, with chapters focused on the various locales in which he resided, including Colorado, New York, Ohio and Washington, DC. While Plato had an intriguing idea for mapping addresses in rural America, he lacked the business acumen to market his product, as well as the ability to identify trustworthy and useful partners for his business endeavors.

Clock and Compass places the work of John Byron Plato in historical context and makes for an engaging read. The text is well written and illustrated with numerous maps and diagrams, along with detailed notes. While it is in some sense a biography of Plato himself, the main focus of the monograph is on the practical problem of how to define locations and provide directions to specific addresses in rural America, in the era of transition to the widespread use of trucks and automobiles. However, due to its relatively narrow focus, only those with specific interests in its topic or the history of twentieth century American cartography are likely to read this book. While interesting and informative, like its principal subject, this book on the Clock System is also likely to remain a footnote.