DOI: 10.14714/CP101.1829

© by the author(s). This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0.

Review of Emma Willard: Maps of History

Edited by Susan Schulten

Visionary Press, 2022

248 pages, 139 maps and graphics, plus a folded 100 × 67 cm poster

Hardcover: $98.00, ISBN 979-8-9861945-0-9

Review by: Mark Monmonier (he/him), Syracuse University

Perhaps best known as a women’s rights activist, Emma Hart Willard (1787–1870) was also an elementary and secondary educator and a successful creator of instructional materials: endeavors to which she directed most of her energy, with impressive results. Willard’s specialties were geography and history, and she believed that to learn history properly, students needed a systematic presentation of facts, processes, geographic settings, actors, and impacts. To these ends, she relied on her skill as an illustrator. Because her experiences and accomplishments were distinctive, Willard is rightly praised as a graphics pioneer: a visionary, if you will. Some of her presentations were maps, but many were data graphics, typically two-dimensional or perspective time-series graphs, in which the time axis was paramount.

The publisher, aptly named Visionary Press, has also recently released two other volumes, celebrating graphic visionaries Florence Nightingale and Étienne-Jules Marey. All three volumes are part of the Information Graphic Visionaries series founded by R. J. Andrews, the series editor. With degrees in mechanical engineering as well as an MIT MBA, Andrews is an accomplished designer, “data storyteller,” and entrepreneur. Credit also goes to Lorenzo Fanton, the skilled designer and freelance art director who oversaw production.

The overall look of Emma Willard: Maps of History is impressive. Although the front matter makes no claim to acid-free paper, its sturdy Fedrigoni Arena pages (white paper with a rough finish), large trim size (19.9 × 27.9 cm), and pleasingly patterned dark rose endpapers strike a note of elegance and durability. Bracketing the pages are stiff boards embellished with a black-and-brown facsimile excerpt from Willard’s iconic poster “The Temple of Time” that is (according to the publisher’s website) “printed on book cloth with gold foil stamp lettering.” No less impressive is the book’s internal design, in which a narrative essay on Willard’s life, work, and impact (15–114) precedes a facsimile section with examples of her key cartographic works, mostly atlases. Reproduced in full color, these facsimile pages are either full-size or only slightly reduced, with a single fold-out page replicating a fold-out in the original.

Captured from holdings in the David Rumsey Historical Map Collection, now in the Stanford University Library, many of the facsimile pages are framed by portions of their original atlas’s binding and nearby pages, laid flat for the camera. Warts-and-all facsimiles connote authenticity by capturing the foxing of the paper, irregularities in inking, and unprinted facing (versa) pages, which avoid annoying read-through and attest to the complexity of double-sided hand-colored map reproduction in the early nineteenth century. It is useful for the reader to see, as representatively as possible, the works analyzed in the essay.

The cover identifies Susan Schulten as the volume’s editor, which suggests that she played the dominant role in selecting specific works for the facsimile section as well as the illustrations that accompany her long essay “A Graphic Mind,” on Willard’s life and work. As she makes clear in the “Acknowledgments,” Schulten was approached by Andrews to develop a short book on Willard’s graphics. She was an obvious choice, having analyzed Willard’s work in a July 2007 article in the Journal of Historical Geography (Schulten 2007) and devoted three decades to exploring the interconnections that existed between mapping, public education, and academic scholarship in America during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. That Andrews did not recruit her until late 2020 confirms both her readiness for the endeavor and the efficiency of Andrews, Fanton, and their Visionary Press colleagues in setting an efficient production schedule and maintaining outstanding quality control.

Map historian Matthew Edney, who guided the massive History of Cartography Project after David Woodward’s untimely death in 2004, contributed an incisive three-page Foreword that positions Willard in the intellectual context of the nineteenth century’s discontent with traditional descriptions and explanations. Edney underscores the difficulties women educators faced in carving out a fuller and more influential role in children’s education as well as the importance of improved technologies of graphic reproduction that allowed a closer integration of verbal and graphic discourses. Though Willard took full advantage of these technologies, by century’s end her innovations were submerged by intellectual currents she had helped promote.

Schulten’s essay—its title, “A Graphic Mind,” is fully appropriate—explores Willard’s substantial contributions to the education of girls in nineteenth-century America and to visual learning more widely. Visual explanation, Willard argued, was an effective way to engage students, who, by making their own maps, could better assimilate and understand spatial relationships. Although some educators saw student maps largely as decorative art, Willard believed that maps could challenge simplistic chronologies by illustrating evolving stages of historical knowledge.

Over the years, Willard played multiple roles in elementary and secondary education. She opened her own schools, the Middlebury Female Seminary, in Vermont in 1814, and the Troy Female Seminary, in New York State in 1821; her use of “Seminary” in their names signaling an eagerness to experiment with new approaches. Willard’s own pedagogic repertoire included moral philosophy and advanced mathematics, as well as geography and history. Her textbooks and school atlases were pitched toward a national audience, and, as an entrepreneur, she struck a collaborative endeavor with pedagogic author William Channing Woodbridge (1794–1845), whose contribution focused on modern geography while Willard emphasized the ancient world.

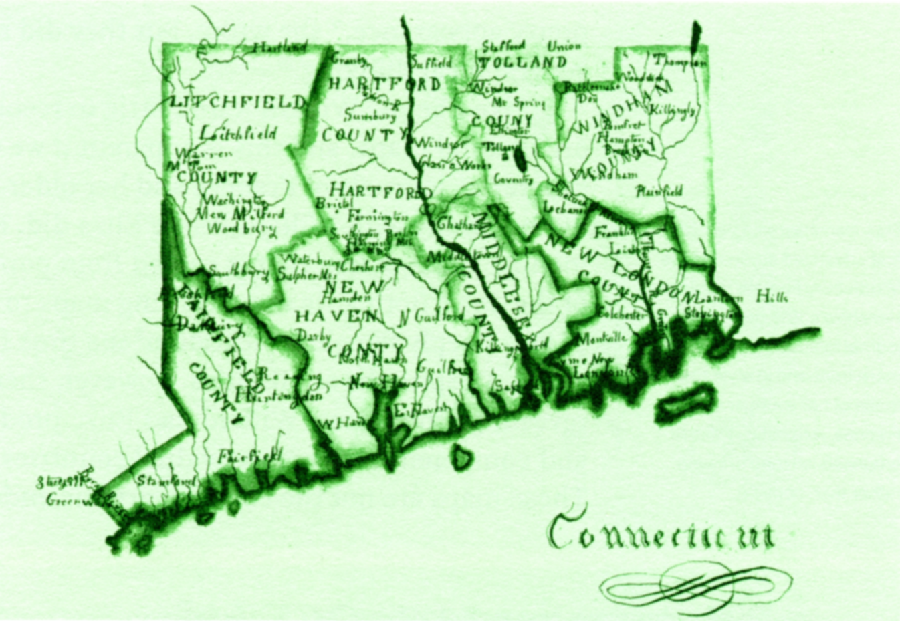

The book’s facsimile section provides numerous illustrations for Schulten’s long essay. Repeated at appropriate points as excerpts or in their entirety but at a smaller size—alongside student maps and illustrations from other textbooks of the period or shortly thereafter—these images enhance her discussion of the creation, purpose, or impact of Willard’s more important graphics. This purposeful redundancy obviates the need for readers to flip forward to the facsimile section to appreciate the structure and symbols of exemplars presented in context in the second half of the book. Facilitating this integration of text and graphics are thoughtfully designed pages with abundant white space. And because images in the essay section are redundant, they are efficiently reproduced in black and flat-green inks, rather than in full color.

Green, the reader quickly discovers, is a leitmotif tint for the Willard volume, distinguished from the robin’s-egg blue used for the Nightingale book and the medium blue used for the Marey volume. Section and subsection titles, with white lettering on a green background, introduce the key parts, and surrounding the elegant binding is a detachable green wrapper, only 70 percent as tall and lettered in crimson (though it seems intended as a dust jacket of sorts, it might more accurately be described as a dust vest). My key criticism is of the designer’s obsession with green, which creates a distinctive look and reinforces the design devised for the series, but also undermines the legibility of images in the essay section, which would work better in simple black and white.

Although a full-color reproduction of this map, by a fourteen-year-old student at the Middlebury Female Academy, appears later in the book (on page 231), this slightly smaller green-and-black version is inserted on page 31, near Schulten’s discussion of artistic styles prevalent in the early 1820s. Although other illustrations in the long-essay section are similarly muddled by the green leitmotiv adopted for the Willard volume, their useful proximity to the relevant part of the essay makes them more than a graphic conceit.

The facsimile examples section, which follows the essay, has three parts. “Atlases” (117–190), which spans the eleven years between Willard’s thirty-ninth and fiftieth birthdays, consists of three atlases, from 1826, 1827, and 1836, each designed to accompany a specific geography textbook. These three relatively thin atlases are reproduced completely, cover to cover, at actual size or 75-percent of the original size. The second and third parts are shorter segments focusing on “Classroom Charts” (192–209) and “Textbook Graphics and Graphic Appendix” (210–233).

The “Atlases” section begins with Willard’s Atlas to Accompany Geography for Beginners (1826), Geography for Beginners being her own textbook—the atlas’s large-page format nicely complements the textbook’s small-page format. Between the second and third atlases is “A Series of Maps to [accompany] Willard’s History of the United States,” published in 1829 and reproduced at 80 percent of actual size. A two-page “Introductory Map” highlights the “Locations and Wanderings of the Aboriginal Tribes” before the advent of Europeans in 1492. On the nine maps that follow, flow lines representing specific trans-Atlantic voyages complement labels and colored boundaries for specific land grants, colonies, states, and territories to describe “epochs” dated 1578, 1620, 1645, 1692, 1735, 1763, 1776, 1789, and 1826. The succession of epochs portrays Willard’s conception of the country’s evolution as a natural, inevitable process—a “Manifest Destiny” that accords with her strong nationalism and devout Christianity. And as Schulten notes, an earlier edition, released in 1828, was in effect the first historical atlas of the United States.

The “Classroom Charts” that follow are reductions of larger images, one of which is inserted loosely in the book as a folded, full-size poster. Appropriately named “The Temple of Time,” this huge 1846 poster (100 × 67 cm) is a perspective drawing of a classic temple with ionic pillars topped by scrolled capitals supporting a pediment and ceiling, and an implied temporal axis advancing toward the viewer from a wall at the center labeled “The Creation 4004” and surrounded by parts progressively less temporally distant—an obvious rejection of science’s emerging sense of geologic time. Willard’s intricate drawing reflects a biblical chronology whereby progressively larger pillars representing specific centuries emerge toward the left and the right. Pillars on the left are named for events or specific people. More recent centuries with larger pillars are in the foreground, and on each pillar the names of more ancient people or events are placed toward the bottom and the more recent are toward the top. Dates accompany names, for example, “Continental Congress, 1776, Independence” and “1492 Discovery of America.” Pillars on the right, which also represent centuries, include names of persons and for more recent individuals, their years of prominence, for example, “David” in the eleventh century BCE, “Jenghis [sic] Khan, 1206–27,” and “Napoleon, 1804–14.” On the temple floor next to the columns on the left are events such as “Charles I executed, 1649” and “Alexander dies 323 [BCE],” and on the floor on the right are significant battles, for example, Hastings and Antioch in the 11th century. Between these peripheral streams of events are channels for individual countries, in pink, yellow, orange or blue, and dividing or merging through time. More names appear in the ceiling, divided into rows of tiles for “Statesmen,” “Philosophers, Discoverers &c,” “Theologians &c,” “Poets, Painters &c,” and “Warriors.” An orange inverted U spanning pillars for the first century CE is labeled “Jesus Christ” on the ceiling. For readers who find this paragraph confusing—I imagine this might include nearly all of you—a zoomable graphic at the Stanford University Library website invites exploration of the poster’s details. Close inspection of the facsimile will reveal that apparent flaws in its printing were inherited from the original, in the David Rumsey Map Collection. Visionary Press’s Italian printer did an outstanding job reproducing this and the book’s other facsimiles, all from the Rumsey collection.

A somewhat smaller version of The Temple published three years later is similar in perspective but with vertical sections rather than the larger diagram’s classical ionic pillars. Reproduced across facing pages (204-205) at about a third its original dimensions (62 × 86 cm), “Willard’s English Chronographer” (1849) focuses on Britain’s saints, heroes, and royalty. Although the framework of a temple is apparent, historic time begins markedly more recently than the biblical 4004 BCE. Indeed, at the center, history emerges from a darkly mysterious “Roman Empire” that resembles a subway tunnel, and the ceiling’s ten categories of personal prominence includes “Remarkable Women.” Below the three-paragraph introduction, a much-reduced photo (6.3 cm wide) offers a concise summary of the poster’s temple-like structure, while on the facing page (recto) a full-size detail excerpt encompassing only 10 percent of the Chronographer’s area provides a sense of the original print’s aesthetics and information content. Schulten calls the graphic a “labor of love” as well as a reflection of Willard’s appreciation of “Anglo settlement in North America.” Her assertion that it “has long been assumed to have been lost” and is “republished here for the first time” raises questions about its publication, promotion, and dissemination, as well as this particular artifact’s provenance. It would be good to know more.

The scholarly apparatus at the back includes a 140-item “Endnotes” section, a one-page “Selected Bibliography,” and a page and a half of “Image Credits.” All are reasonably complete and useful, but can the absence of an index be a new trend in scholarly publishing? Indeed, I can hardly complain insofar as my own publisher, a fully competent university press, just last year released my book sans index. I was told none was needed, which I believed at the time—before it occurred to me that an index can be particularly useful to a reviewer intent on some last-minute fact-checking.

The back matter also includes three pages of “Acknowledgements,” two of which applaud the generosity of several hundred contributors to a crowdfunding campaign organized by Andrews and Fanton. Though I regret my name is not among them—the appeal must have slipped beneath my radar—I can at least recommend the book strongly. Not only well written and carefully edited, Emma Willard: Maps of History is a joy to hold and peruse.

And as a publishing event, if you will, it is a noteworthy departure from today’s typical medium-length scholarly map history burdened with a price tag that will confine it to a small sale, mostly to libraries. Might crowdfunding be the new subvention?

REFERENCE

Schulten, Susan. 2007. “Emma Willard and the Graphic Foundations of American History.” The Journal of Historical Geography 33: 542–564. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhg.2006.09.003.