DOI: 10.14714/CP105.1959

© by the author(s). This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0.

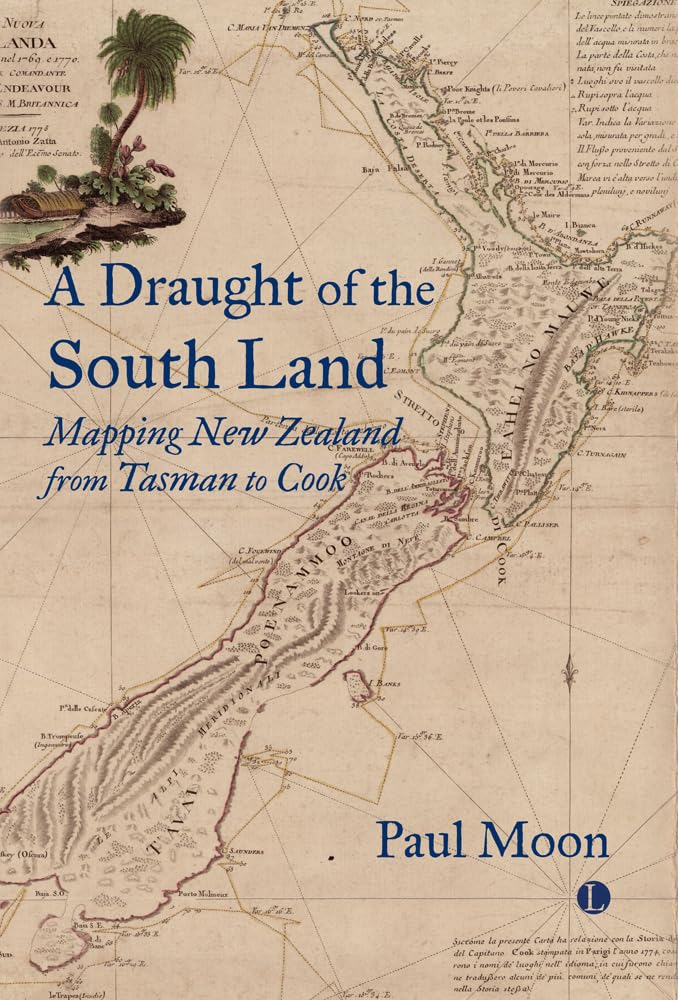

Review of A Draught of the South Land: Mapping New Zealand from Tasman to Cook

By Paul Moon

The Lutterworth Press, 2023

200 pages, including maps and diagrams

Hardcover: $90.00, ISBN: 978-0-7188-9721-5

Paperback: $30.00, ISBN: 978-0-7188-9720-8

ePub: $23.99, ISBN: 978-0-7188-9722-2

Review by: Brooks Groves (he/him)

In this insightful book, A Draught of the South Land: Mapping New Zealand from Tasman to Cook, historian Paul Moon meticulously uncovers the cartographic history that not only charted New Zealand but also shaped its encounter with European powers. Moon, a distinguished scholar of New Zealand’s colonial and indigenous histories, crafts a narrative that extends far beyond maritime exploration, highlighting the strategic and often contentious role of cartography in imperial expansion, cultural encounter, and geopolitical strategies.

Moon begins by setting the stage within the Age of Discovery, a period roughly spanning the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries that is characterized by significant advancements in navigational technology and intense competition among European nations eager to expand their realms and control trade routes. Central to this was the Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie, or VOC), founded in 1602 as one of the first joint-stock trading companies—a pioneering innovation that distinguished it from previous trading entities, which were merely groups of individual traders. The joint-stock structure allowed the VOC to pool resources from multiple investors, spreading risk and enabling more substantial and sustained investment in trade and exploration.

The VOC epitomized the use of cartography as a strategic tool to assert and expand Dutch imperial interests, establishing a global trade network that connected Europe with Asia, Africa, and the Americas. Within this framework, Hessel Gerritsz emerged as a pivotal figure. As the first exclusive cartographer of the VOC and considered by some as the chief Dutch cartographer of the seventeenth century, Gerritsz’s role was crucial. His detailed maps were not only practical tools for navigation and trade, but also potent symbols displayed in diplomatic courts to impress both domestic and foreign viewers, asserting Dutch maritime and commercial supremacy. Gerritsz’s work exemplified the integration of cartographic skill with imperial strategy, reinforcing the VOC’s position as a dominant force in global trade and exploration.

These maps—replete with strategic embellishments—exaggerated the size and potential wealth of Dutch claims to deter rivals and attract investment. Gerritsz’s creations highlighted the newly “discovered” territories in relation to existing trade routes, aligning perfectly with the VOC’s vision of economic dominance and diplomatic prowess. The maps were intricately woven into the fabric of Dutch imperial ambitions, functioning on multiple levels: as navigational aids, territorial markers, and artifacts of diplomacy.

Moon recounts the voyage Abel Tasman undertook in 1642, sailing his ships along the west coast of New Zealand. One of a series of exploratory endeavors sponsored by the VOC, it was not merely a voyage into uncharted waters, but a mission driven by the allure of wealth and strategic imperatives. The company’s primary ambition was to expand their lucrative spice trade and to probe rumored southern lands said to be rich in gold and other commodities. This journey—the first European encounter with New Zealand—also produced the first European maps of these large and diverse lands. Tasman’s maps were not only instrumental in the VOC’s expansionist strategy but were pivotal in integrating the region into the broader scope of European maritime ambitions, sparking interest in further exploration in the Pacific.

Paul Moon provides an intriguing examination of the extended lull between Abel Tasman’s 1642 encounter with New Zealand and James Cook’s more scientifically rigorous expeditions beginning in 1769. During this interim, lasting over a century, European cartographers, working half a world away, relied on hearsay and the often-sketchy charts of Tasman and others, resulting in maps that were more speculative than accurate. The VOC’s Hessel Gerritsz contributed significantly to this period of speculative mapping. His maps, like those of many of his contemporaries, sometimes included fantastical elements—mythical creatures, speculative landmasses, and fictionalized depictions of the indigenous Māori—reflecting the European fantasies about distant lands.

These representations painted New Zealand as a place of wonder and mystery, and an alluring blank canvas for European aspirations and fears. The speculative nature of Gerritsz’s maps, while not unique, highlights the era’s blend of curiosity, ambition, and the limited availability of accurate information. Moon’s analysis underscores how the conception of New Zealand took shape in the minds and maps of Europeans during this period, setting the stage for Cook’s later, more empirical explorations.

Cook’s voyages—which Moon contrasts sharply with the earlier era—were underpinned by Enlightenment values and equipped with advanced scientific instruments and were aimed at generating accurate knowledge and dispelling myths. These expeditions marked a turning point—a shift away from the realm of imagination to one of empirical inquiry and detailed, systematic cartography.

The earlier, speculative, maps, while inaccurate, were not merely errors in cartography; they reflected the European zeitgeist, a testament to the era’s blend of curiosity, ambition, and ignorance. Moon’s analysis of this period reveals how the conception of New Zealand took shape in the minds and maps of Europeans and showcases the profound impact these imaginings had on the eventual European engagement with the actual land and peoples of New Zealand. At the same time, however, significant cultural and intellectual transformations in Europe were changing and expanding the European worldview.

James Cook’s voyages represent that fundamental shift in European exploration. The ostensive rationale for Cook’s 1768 voyage was observation of the 1769 transit of Venus, but he was also secretly commissioned to seek out Terra Australis: the hypothesized southern continent. Thus, beginning with Cook’s first Pacific expedition, commercial and imperial justifications began to be overlaid with, and joined onto, Enlightenment endeavors aimed at enhancing European knowledge and understanding of the world.

During his comprehensive exploration of New Zealand, Cook employed meticulous survey methods that resulted in significantly more accurate charts. Using new tools like the marine chronometer, which allowed for precise longitude measurements, Cook and his crew undertook a detailed coastal charting project; correcting the earlier, more primitive maps produced by Tasman and his contemporaries. Through these methodical surveys, Cook established that New Zealand consisted of two main islands—which he named the North and South Islands—thus dispelling earlier European beliefs that it might be part of a larger southern continent.

The level of detail in Cook’s maps was unprecedented. For example, he charted the intricate inlets and harbors of New Zealand’s coastlines, often navigating closer to the shore than previous explorers had dared. Cook’s charts were so accurate that some were used well into the twentieth century, a testament to their precision and usefulness.

Cook’s interactions with the indigenous Māori were significantly enhanced by the presence of Tupaia, a Polynesian priest and skilled navigator, who had joined Cook’s expedition in Tahiti. Tupaia’s ability to communicate with the Māori was invaluable, not only in facilitating immediate interactions but also in contributing to a deeper cultural exchange. He helped bridge the cultural gap between Europeans and the Māori, allowing for a more nuanced understanding of the social structures, customs, and languages of the Pacific peoples.

Tupaia’s contributions went beyond mere translation; he provided Cook and his crew with insights into the Polynesian wayfinding techniques and local geographical knowledge, which enriched the European maps with ethnographic details and helped Cook navigate other parts of the Pacific. Recognition of the pivotal importance of indigenous knowledge, such as that brought by Tupaia, challenges the standard narrative of heroic European exploration and solitary discovery, and instead highlights the collaborative nature of exploration.

Moon places emphasis on Tupaia’s role not only to illustrate the collaborative nature of Cook’s voyages but also to underscore what he sees as a critical shift in European exploration—from conquest to scientific inquiry and mutual exchange. This aspect of Cook’s expeditions illustrates a broader Enlightenment-driven curiosity about the world, seeking to understand and document human diversity and the complexity of natural phenomena in a systematic and empirical way.

However, it is important to note that the integration of indigenous knowledge, and the recognition of figures like Tupaia, has only recently come to be acknowledged, much like the recent recognition of the role of Sacagawea in the success of the Lewis and Clark’s expedition. Moon seems to suggest that this shift towards recognizing indigenous contributions was not fully realized or appreciated by the people of the eighteenth century. This perspective challenges the traditional narratives and highlights the often-overlooked contributions of indigenous peoples in these historic voyages.

Cook’s voyages to New Zealand were instrumental in both refining the European maps and in transforming European cultural understanding of the Pacific. His integration of advanced cartographic techniques and genuine cultural exchange with indigenous peoples marked a new era in European exploration, characterized by greater accuracy, respect, and reciprocity.

In the final segment of Paul Moon’s exploration, attention turns to the lasting impact of historical cartography on contemporary issues in New Zealand. Moon begins with the contributions of stay-at-home mapmakers like Gerritsz, whose meticulous work, driven by Dutch imperial ambitions, significantly shaped early European perceptions of New Zealand’s geography. Despite their primitive, but detailed, nature by modern standards, Gerritsz’s maps were instrumental in guiding exploration and colonization efforts, establishing a foundation for subsequent navigational endeavors.

Moon then highlights how maps crafted by explorers like Tasman and Cook, initially designed for navigation, evolved into essential tools for colonial administration. These maps are now frequently referenced in legal disputes, particularly those involving land claims by indigenous Māori communities, underscoring their enduring significance. Gerritsz, alongside Tasman and Cook, emerges as a central figure in shaping the cartographic legacy that continues to influence contemporary discussions on land rights and cultural heritage preservation in New Zealand. This legacy highlights the profound and lasting impact of these historical maps on modern legal and cultural landscapes.

Moon further explains how the precision and detail of Cook’s maps have lent a degree of legitimacy to certain land claims, as these maps often serve as some of the earliest comprehensive records of the geography and human settlements in New Zealand. This not only underscores the legal and historical significance of these maps but also illuminates the complexities surrounding land rights issues, where colonial-era documents are used within modern judicial systems to resolve claims.

Moreover, Moon discusses the role of maps in cultural heritage preservation. The maps are more than just geographical representations; they are cultural artifacts that carry the imprints of cross-cultural encounters and the mingling of Western and indigenous knowledge systems. They help trace the lineage of historical interactions and serve as tools for cultural education and preservation, aiding efforts to revitalize and maintain indigenous languages, place names, and stories that are embedded in the landscape.

The evolution of cartography from traditional methods to modern satellite-based techniques also features prominently in Moon’s analysis. This transition reflects significant technological advancements that have transformed how maps are created and used. Despite these changes, Moon argues that the fundamental role of maps as instruments of knowledge and power remains unchanged. Contemporary satellite maps continue to influence geopolitical strategies and cultural narratives much like their hand-drawn precursors, shaping perceptions and policies at both national and global levels.

Moon also reflects on how these historical cartographic efforts are not static relics of the past but dynamic tools that continue to impact contemporary society. The legacy of these maps extends beyond their original purpose, influencing modern legal, political, and cultural landscapes in profound and lasting ways. This reflection offers a nuanced perspective on the power of maps, emphasizing their role as enduring links between history, knowledge, and power in shaping societies.

In A Draught of the South Land, Paul Moon offers an extensive exploration of the roles of cartography in empire-building and knowledge dissemination, marked by its engaging narrative and thorough research. However, while the book is commendable for its depth and breadth, it is not beyond criticism.

One point of critique is Moon’s heavy reliance on European sources, which, while rich and informative, could be seen as presenting a somewhat Eurocentric view of history. Although Moon acknowledges the contributions of indigenous knowledge through figures like Tupaia, the primary perspective tends to favor the European narratives of discovery and exploration. This approach may leave readers yearning for a more balanced account that elevates non-European voices and perspectives, particularly those of the Māori, whose land and culture were significantly impacted by the events described.

Additionally, some readers might find Moon’s detailed descriptions of cartographic techniques and historical map analysis somewhat esoteric. While these sections underscore the scientific advancements of the period, they can occasionally bog down the narrative, potentially alienating readers who are less familiar with geographic or cartographic jargon.

Despite these criticisms, A Draught of the South Land remains an indispensable resource. It provides a nuanced understanding of how exploration and cartography have shaped not only New Zealand but also the broader dynamics of global history. The book’s exploration of the enduring impact of these maps on contemporary issues adds a layer of relevance, making it a valuable read for those interested in the intersections of history, geography, and politics. Moon’s work is a critical addition to the field, offering insights into the transformative power of maps while highlighting areas where historical narratives can be expanded to incorporate a more inclusive range of perspectives.