DOI: 10.14714/CP79.1240

The Mocking Mermaid: Maps And Mapping In Kenneth Slessor’s Poetic Sequence The Atlas, Part Four

Adele Haft, Hunter College of the City University of New York | ahaft@hunter.cuny.edu

ABSTRACT

Midway through composing his five-poem sequence The Atlas (ca. 1930), the acclaimed Australian poet Kenneth Slessor suddenly wrote “Southerne Sea” in his poetry journal. He’d just chosen John Speed’s famous double-hemisphere map, A New and Accurat Map of the World (1651/1676), as the epithet of his fourth poem “Mermaids.” Unlike the cartographic epigraphs introducing the other poems, however, this map has little to do with “Mermaids,” which is a riotous romp through seas of fantastic creatures, and a paean to the maps that gave such creatures immortality. The map features a vast “Southerne Unknowne Land,” but no mythical beasts. And while it names “Southerne Sea” and “Mar del Zur,” neither “Mermaids” nor The Atlas mentions Australia or the Southern Sea. Moreover, Slessor’s sailors are “staring from maps in sweet and poisoned places,” yet what the poem describes are “portulano maps,” replete with compass roses and rhumb lines—features notably absent on A New and Accurat Map of the World. My paper, the fifth part of the first full-scale examination of Slessor’s ambitious but poorly understood sequence, retraces his creative process to reveal why he chose the so-called Speed map. In the process, it extricates the poem from what Slessor originally called “Lost Lands Mermaids” in his journal, details his debt to the ephemeral map catalogue in which he discovered his epigraph, and, finally, offers alternative cartographic representations for “Mermaids.” Among them, Norman Lindsay’s delightful frontispiece for Cuckooz Contrey (1932), the collection in which The Atlas debuted as the opening sequence.

KEYWORDS: Kenneth Slessor (1901–1971); Cuckooz Contrey (1932); The Atlas sequence (ca. 1930); “Mermaids”; poetry—twentieth-century; poetry—Australian; poetry and maps; cartography—seventeenth-century; John Speed (1552–1629); Norman Lindsay (1879–1969)

Man … has been fascinated by the mermaid; by her eternal youth, her strange, unnatural beauty; her allure; and by the mysterious ocean wherein she dwells. Her delightful custom of combing her long tresses, mirror in hand, and the magic of her voice … these, too, have … often blinded him to her true nature. For the mermaid is the femme fatale of the sea; she lures man to his destruction, and usually he goes unresisting to his doom.”

—Gwen Benwell and Arthur Waugh, Sea Enchantress: The Tale of the Mermaid and Her Kin (1965)

I have heard the mermaids singing, each to each.

I do not think that they will sing to me.

—T. S. Eliot, “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” (Poetry, June 1915)

DISCOVERY

Two decades ago, I discovered the Australian poet Kenneth Slessor while searching for “maps” in Columbia Granger’s World of Poetry database. Among the hundreds of entries citing the word, one line leapt off the screen—“staring from maps in sweet and poisoned places.” It came from “Mermaids,” the exuberant fourth poem of Slessor’s five-poem sequence The Atlas (ca. 1930). Reading the poem brought other delights. Seas filled with Mermaids, Anthropophagi and Harpies dancing on the shores, portolan charts with “compass-roses … wagg[ing] their petals over parchment skies,” not to mention Slessor’s obvious delight in conflating the imagery of early maps with what mariners actually experienced. I was hooked, especially after realizing that “Mermaids,” like most of the sequence, begins with an introductory quote or epigraph from an important and beautifully illustrated seventeenth-century map.

And there lay the problem. Once I understood how map-obsessed Slessor was, it became impossible to treat “Mermaids” in isolation as if it were a self-contained poem like Earle Birney’s “Mappemounde” (Haft 2002), Grevel Lindop’s “Mappa Mundi: The Thirteenth-Century World-Map in Hereford Cathedral” (Haft 2003a), or Marianne Moore’s “Sea Unicorns and Land Unicorns” (Haft 2003b), each of which also imagines fabulous sea-creatures through a cartographic lens. “Mermaids” had to be viewed in relationship to the poems around it, and to The Atlas as a whole.

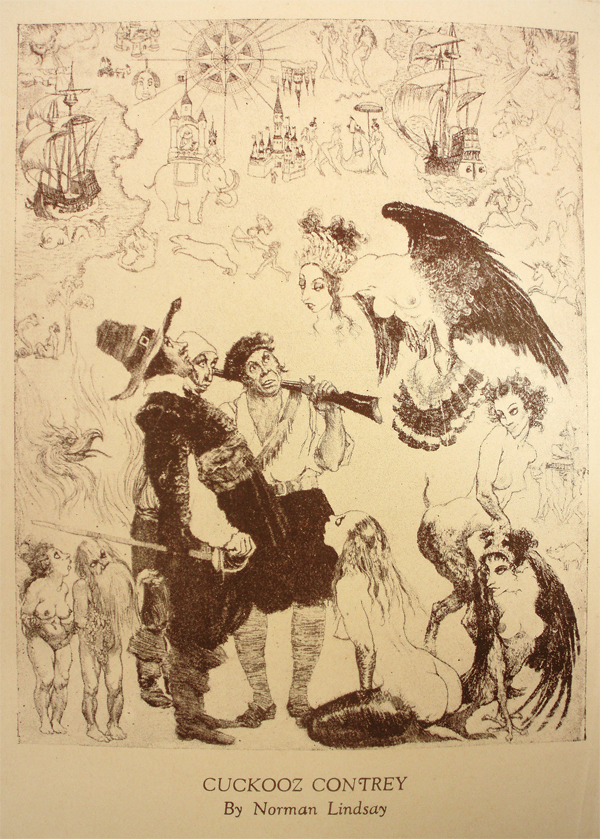

In four earlier issues of Cartographic Perspectives I have begun that journey. My “Introduction” (Haft 2011) focused on Slessor’s literary accomplishments, particularly Cuckooz Contrey (1932), his third solo collection which opened with the recently minted Atlas sequence. Since much of his early poetry was illustrated, at least two of the artists whom we encountered in the introduction reappear here. The first is Slessor’s mentor, Norman Lindsay (1879–1969), the famously controversial bohemian artist/writer popularized, however inaccurately, in the 1993 film Sirens. According to Slessor, Lindsay’s generous collaborations enabled the artist/writer to “exercise more influence … on numbers of this country’s poets than any other single individual in Australia’s history” (Slessor 1970, 111–112). Lindsay repeatedly alludes to “Mermaids” in the frontispiece he created for Cuckooz Contrey. The second prominent artist is poet/illustrator Hugh McCrae (1876–1958), who admired Slessor’s and Lindsay’s works as much as they admired his (Slessor 1970, 92–110; Lindsay and Bloomfield 1998, 40–41, 55–64). All three life-long friends contributed to the short-lived magazine Vision: A Literary Quarterly (Johnson, Lindsay, Slessor 1923–1924), which promised its youthful readers poetry and prose that “liberate the imagination by gaiety or fantasy” (Vision 1, May 1923, 2; see Lindsay 1960, 84; Dutton 1991, 58 and 71). Cavorting through the four issues of Vision were Norman’s drawings of mermaids, fauns, nymphs, and centaurs—lustful creatures of Classical and Anglo-Saxon mythology that he and McCrae helped relocate in Australian literature. Then there’s Captain Francis Joseph Bayldon (1872–1948), the maternal uncle of Slessor’s first wife, Noela. As practical as the others were dreamers, Bayldon was a master mariner, accomplished hydrographer, and writer/lecturer specializing in Australian maritime history and exploration (Phillips 1979). Even so, he became “a major influence” on Slessor’s “poetic career” (Dutton 1991, 142). For while composing The Atlas, Slessor discovered that weekly visits to Bayldon’s home in Sydney gave him access not only to the old sea-captain’s “astonishing knowledge of nautical things” (Kiernan 1977, 7; Slessor, Haskell, and Dutton 1994, 362), but also to the captain’s “magnificent nautical library” (Slessor 1970, 192), now preserved in the Mitchell Library of the State Library of New South Wales. Slessor’s biographer Geoffrey Dutton thought that “Slessor took his notebook along to Captain Bayldon’s,” because “it is full of jottings from old maps and books, lists of galleons, sloops, flying fish, sea monsters, battles and mermaids” (Dutton 1991, 144). More likely, Bayldon lent Slessor the work that inspired The Atlas and became its ultimate source—an illustrated and unusually lyrical catalogue titled Old Maps of the World, or Ancient Geography; a Catalogue of Atlases & Maps of All Parts of the World from XV Century to Present Day (Francis Edwards 1929). With its poetic advertisements of maps and cartographers as well as its attention to the period vocabulary of its items, Old Maps of the World proved irresistible to a word-smith and verbal image-maker like Slessor. What makes The Atlas unique is its poet’s response not to the physical sensation of seeing or touching maps, but to a catalogue’s impassioned description of their allure; for without that piece of ephemera, “Mermaids”—like the other poems of the sequence—simply would not exist. Yet the catalogue used by Slessor, like the creatures of his poem, is “GONE like the cracking of a bubble.” No trace of it can be found in the Bayldon Collection, the Slessor Papers at the National Library of Australia, the Slessor Collection at the University of Sydney, or any public library in Australia (Australia Trove, National Library of Australia).

As for The Atlas poems themselves, my article “Who’s ‘The King of Cuckooz’?” (Haft 2012a) dealt with the sequence’s opening poem, the one most like “Mermaids” in tone, even though “The King of Cuckooz” focuses on a 1620 reconnaissance map of Algiers by the gunner/surveyor/cartographer Robert Norton. “John Ogilby, Post-Roads, and the ‘Unmapped Savanna of Dumb Shades’” (Haft 2012b) examined Slessor’s second poem, “Post-roads.” If “Mermaids” envisions seas filled with mythical creatures, “Post-roads” recasts dancer/translator-turned-publisher/cartographer John Ogilby into a beatific Sisyphus mapping the roads of eternity. “Imagining Space and Time in Kenneth Slessor’s ‘Dutch Seacoast’ and Joan Blaeu’s Town Atlas of The Netherlands” (Haft 2013) explored one of Slessor’s eight “least unsuccessful” poems. But if “Dutch Seacoast” became the central poem of The Atlas, that was not Slessor’s original intention: he’d designed the sequence to showcase “Mermaids” as its centerpiece.

Why “Mermaids” came fourth occupies the beginning of this present paper, which reprints the poem and briefly discusses the poem’s subject, artistry, and critical responses before turning to the difficulties that Slessor encountered when trying to conceptualize what he called “Lost Lands Mermaids.” The poem’s cast of characters then comes into focus, followed by an introduction to the maps in “Mermaids.” After retracing Slessor’s search for the right epigraph, the paper evaluates his choice—the famous world map associated with the English historian/cartographer John Speed—and investigates the complex relationship between Old Maps of the World and the drafts of “Mermaids” in Slessor’s poetry journal. Next, it compares the published poem with the so-called Speed map, and then confronts the disparities between the two before concluding that the poem, despite its epigraph, has many cartographic inspirations. Finally, the paper shows how Slessor’s artist friends, in contemporary illustrations of his work, combined maps and mermaids, though not necessarily in ways appropriate to the poem itself.

KENNETH SLESSOR’S “MERMAIDS”

Let’s begin with the poem itself:1

“A new and Accurat Map of the World, in two Hemispheres, Western and Eastern, with the Heavens and Elements, a Figure of the Spheare, the Eclipse of the Sunne, the Eclipse of the Moon.” — J. Speed, 16752

Once Mermaids mocked your ships

With wet and scarlet lips

And fish-dark difficult hips, Conquistador;

Then Ondines danced with Sirens on the shore,

Then from his cloudy stall, you heard the Kraken call,

And, mad with twisting flame, the Firedrake roar.

Such old-established Ladies

No mariner eyed askance,

But, coming on deck, would swivel his neck

To watch the darlings dance,

Or in the gulping dark of nights

Would cast his tranquil eyes

On singular kinds of Hermaphrodites

Without the least surprise.

Then portulano maps were scrolled

With compass-roses, green and gold,

That fired the stiff old Needle with their dyes

And wagged their petals over parchment skies.

Then seas were full of Dolphins’ fins,

Full of swept bones and flying Jinns,

Beaches were filled with Anthropophagi

And Antient Africa with Palanquins.

Then sailors, with a flaked and rice-pale flesh

Staring from maps in sweet and poisoned places,

Diced the old Skeleton afresh

In brigs no bigger than their moon-bunched faces.

Those well-known and respected Harpies

Dance no more on the shore to and fro;

All that has ended long ago;

Nor do they sing outside the captain’s porthole,

A proceeding fiercely reprehended

By the governors of the P. & O.

Nor do they tumble in the sponges of the moon

For the benefit of tourists in the First Saloon,

Nor fork their foaming lily-fins below the side

On the ranges of the ale-clear tide.

And scientists now, with binocular-eyes,

Remark in a tone of complacent surprise:

“Those pisciform mammals—pure Spectres, I fear—

Must be Doctor Gerbrandus’s Mermaids, my dear!”

But before they can cause the philosopher trouble,

They are GONE like the cracking of a bubble.

After the angst with which “Dutch Seacoast” ends, “Mermaids” delights us with its bouncy rhythms, varied rhymes, and gallery of mythic creatures that once entertained sailors and adorned their maps. A celebration of vitality and wonder, overlaid with “a new satiric nuance and dryness of tone” (Burns [1963] 1975, 24), the fourth poem of The Atlas pits new science against old science, only to find “scientists now” complacent, patronizing, pedantic, and utterly lacking in romance. For them, the seductive mermaid is merely one of “those pisciform mammals”—like the dugongs, who inhabit the shallow, tropical waters from East Africa through the Philippines; or the manatees, their West African and New World relatives whom the Conquistadors mistook for mermaids (Ellis 1994; see NLA MS 3020/19/1/1373 for “1494”). Once classified as “Pisciformae” (“fish-shaped”: Ellis 1994, 90), such homely and placid mammals held as much allure for Slessor as “Doctor Gerbrandus’s Mermaids.”4 Throughout the poem, Slessor combines such light-hearted satire with a wistfulness for a more daring and imaginative era, when sailors braved unknown seas in “brigs no bigger than their moon-bunched faces.” Yet Slessor hasn’t entirely given up hope for a world that inspires awe rather than scientific skepticism or tourists’ passive acceptance of whatever experts on their cruise ship happen to “remark.”5 In his Vision days, Slessor might have suggested that creatures like mermaids exist for those who believe in them (e.g., “Realities”: Slessor, Haskell, and Dutton 1994, 58–59). He says as much in a draft of “Mermaids”: “sailors undoubtedly saw them because they/ believed in them but as soon as they asked/ “Is that a mermaid”/ they vanished/ like a bubble snapping” (June 1, ‑s137). The final lines of “Mermaids,” however, shift the perspective: mermaids are “pure Spectres” for those who haven’t the imagination to believe.

Douglas Stewart recognized a shift in “Mermaids” and interpreted it as one of Slessor’s “break-through[s] into the poetry of the twentieth century” (Stewart 1964, xxx):

The difference between Cuckooz Contrey and the Australian poetry which had preceded it might be seen in … the change of outlook demonstrated in the subject of mermaids, where they are touched upon in “The Atlas.” To Hugh McCrae—and rightly for his purposes—a mermaid would have been a serious matter; Slessor drily notes that such an apparition would have hardly been credible to the passengers of the P. & O.

Which is why Stewart began his influential anthology Modern Australian Verse with Slessor’s poetry from 1930 on, and why he chose “Mermaids” in particular.

Like Stewart, Herbert Jaffa sensed the poem’s significance within Cuckooz Contrey, but regarded “Mermaids” nostalgically. However “light” its spirit, however much its “high humor” resembles that of “The King of Cuckooz,” Jaffa concluded (1971, 83):

We leave the poem with some feeling of sadness and sense of loss. Once there was a time for imagining and dreaming; now it is no more: now we live with the facts, the literalness of things. We will discover this sadness and sense of loss with increasing frequency and depth in many poems of the middle period [1927–1932].

Dennis Haskell, on the other hand, approaches the poem more optimistically in The Sea Poems of Kenneth Slessor (Slessor et al. 1990, 7):

‘The Atlas: Mermaids’ establishes the sea as the site of the imagination, and of reality as it exists in full human awareness, uncontainable by the narrow vision of scientists or the mapmakers of ‘The Atlas: Dutch Seacoast.’

In terms of technique, “Mermaids” showcases “Slessor’s skill in utilizing the resources of rhyme and metre” (Thomson 1968, 39), particularly the “aaabbccb” rhyme scheme of the initial stanza (June 22, -s160). The sheer variety of stanza and line lengths, of meters and rhyming schemes, befits the variety of fabulous creatures dancing through “Mermaids.” Ronald McCuaig praises the “tempo di can-can…where words dance” in lines like “Those well-known and respected Harpies… On the ranges of the ale-clear tide” (quoted in Thomson 1968, 55). And Stewart declares that Slessor contributed the “ub” sound to the music of English poetry (Stewart 1969, 152), especially in his use of “bubble” in “bubble-clear/ canals of Amsterdam” (“Dutch Seacoast”) and “like the cracking of a bubble” (“Mermaids”). As for its broader appeal, “Mermaids” has appeared in more anthologies of Australian verse than the other Atlas poems. Besides Stewart’s Modern Australian Verse, it graces Judith Wright’s New Land, New Language (1957), though without its epigraph. And Haskell chose “Mermaids” for Kenneth Slessor: Poetry, Essays, War Despatches (Slessor and Haskell 1991) as well as for The Sea Poems of Kenneth Slessor, illustrated with Mike Hudson’s delightful engraving of a mermaid holding a mirror while combing her locks (Slessor et al. 1990, 21) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Mike Hudson’s wood-engraving of “Mermaids” in The Sea Poems of Kenneth Slessor, edited by Dennis Haskell (Slessor et al., Canberra: Officina Brindabella, 1990, 21). With her long locks, comb, and mirror (symbol of beauty and vanity), Hudson’s mermaid retains her medieval and early modern features. Reproduced from The Sea Poems of Kenneth Slessor.

“LOST LANDS MERMAIDS”

Despite the poem’s playfulness, Slessor found composing “Mermaids” to be the most difficult part of The Atlas. Several entries in his poetry journal reveal that he intended the poem to be the centerpiece of his sequence (March 18, -s76; March 28–29, -s83–84; April 3, -s88; April 23, -s101; April 29, -s105). Yet he couldn’t decide on a title. On the fifth page of his Atlas drafts, for instance, a question mark follows his first attempt (March 2, -s62): “Ballade of Vanished Countries?” His second attempt, “lost countries,” suggests the name of a list rather than the title of a poem (March 6, -s65). His hybrid title “Lost Lands Mermaids” (March 18, -s76) hints at two potentially competing ideas: one focused upon the land and its inhabitants; the other, on the sea and its denizens. Although “Lost Lands” quickly rose to the fore (March 28, -s83; April 3, -s88), and although Slessor was busy sketching out its stanzas (April 23–29, -s101 to -s105; insert before May 3, -s108; insert after July 11, -s177; May 31, -s136), “Lost Lands” ultimately joined “Seafight” as the two Atlas poems that remained unfinished by December 6, 1930 (see “August 9,” -s206). Once he’d completed the latter (August 10–30, -s207 to -s230), Slessor crossed out “Sea-fight” in that entry. But “Lost Lands” never resurfaced in the journal, let alone in The Atlas. The stanzas Slessor was sketching (see Stewart 1977, 99–100) eventually morphed into “Lesbia’s Daughter,” which premiered in Five Bells several years later (1939: Slessor, Haskell, Dutton 1994, 128, 358, 398). The change of title says it all: only two lines of Slessor’s “Lost Lands” remain in “Lesbia’s Daughter”—“Where’s the fine music that the fossil men/ Of lost Lemuria brandished on a pen?” As for our poem, Slessor did not return to it until long after he’d abandoned “Lost Lands,” and only after having completed more than half of what we now recognize as “Mermaids.” By then, he had not only written the first three parts of The Atlas, but had quietly shifted the “central” poem into fourth place (May 25, -s132; May 29, -s134).

Without “Lost Lands,” however, neither “Mermaids” nor The Atlas would exist. On the seminal opening pages of The Atlas drafts (February 22 to March 4, -s58 to -s63), Slessor highlights three items with triple XXXs. The second and third relate to “The King of Cuckooz” (“Atlas 5”: March 2, -s62). But the initial item reads: “note vanished empires, lost kingdoms, forgotten lands & provinces, crumbled boundaries” (“Atlas 4”: February 28, -s61). Slessor would later include “The King of Cuckooz Contrey” as one of his lost kingdoms (March 6, -s65). Besides that, what these items have in common is their debt to the 1929 Francis Edwards catalogue Old Maps of the World. Nowhere is this more obvious than in the expanding and overlapping lists of toponyms labeled “lost countries” or “lost lands” that Slessor periodically compiled to jump-start his composition.6 The first list includes “Antient Africa” (March 6, -s65), the only place-name in “Mermaids” (stanza 4). Slessor found its archaic spelling in E. Wells’ A New Map of the North Part of Antient Africa (1700). Although no citation appears in his poetry journal, the catalogue’s item 491 not only features a map with this title but also closely follows the Robert Norton entry used by Slessor for “The King of Cuckooz” (item 487: Francis Edwards 1929, 106; see Haft 2012a). Since Slessor first mentions “Antient Africa” in his journal immediately after his discovery of Norton’s map (“Atlas 6”: March 4, -s63), it’s clear that the earliest pages of his Atlas drafts reflect his engagement with the catalogue from beginning to end, or at least to “Poli Arctici” in item 636 of 852 total (Francis Edwards 1929, 123; March 4, -s63).

While “Mermaids” would ultimately favor sea-creatures over the monstrous races cluttering lands called “unknown” (see Friedman 1981; Haft 1995), the poem does revel in “singular kinds of Hermaphrodites” (stanza 2), and “beaches…filled with Anthropophagi” (stanza 4). Human races endowed with both male and female sexual organs were common enough on medieval manuscript maps (Westrem 2001, 378–379; thea, 397–398), although none of the items in Old Maps of the World actually mentions hermaphrodites or androgini (Friedman 1981, 10). As for anthropophagi, people who “eat people” remained popular on maps, especially once this monstrous race was transposed to the New World and renamed “cannibals” (Reinhartz 2012, 110, 132, 147–148). The third and fourth pages of the Atlas drafts reveal how quickly Slessor discovered references to man-eaters in the catalogue (February 26, -s60; February 28, -s61). “Figures of anthropophagi” comes from item 106—a Mercator atlas containing a map of Brasil by Hondius “adorned with figures of anthropophagi, ships, animals, &c.” (Francis Edwards 1929, 49; detail in Reinhartz 2012, 147), while “anthropophagi in Brasil” comes from item 133—a Ptolemaic atlas with 50 maps, including “Tabulae Terrae Novae, with … anthropophagi in Brasil, &c.” (Francis Edwards 1929, 58; see also 116, item 565).

“Anthropophagi in Brasil” reappears with a check beside it in Slessor’s pivotal “May 29” entry (-s134). Although titled “Lost Lands” (see also August 9, -s206), that entry and the following two pages mark the transition to “Mermaids,” whose outlines are evident by “June 1” (-s137). Slessor’s “May 29” entry includes many other names and phrases recognizable from “Mermaids”: “mermaids,” “dolphins,” “palanquins,” “portolanos” or “portolan maps,” “the Eclipse of the Sunne,” and “compass roses (spreading their green & yellow petals).” Like “anthropophagi,” each of these first surfaced in the opening pages of his Atlas drafts, and each was highlighted with a check.7 The only words not initially checked are “dolphins” and “palanquins” (March 2,-s62), though, like almost everything else in the poem, they are hybrids—at least in name. For unlike fish, the dolphin (Gk delphis) has a womb (Gk delphus), while “palanquin”—one of the exotic words that Slessor found irresistible—is the Portuguese pronunciation of the East Asian word for an enclosed litter that rests on poles, thus allowing an individual to be conveyed on other men’s shoulders. At the center of his “May 29” entry, these two words appear with “mermaids” in phrases heavily bracketed to indicate their importance (‑s134). Once Slessor began to abandon “Lost Lands,” in other words, “Mermaids” quickly revealed itself from the fragments of his earliest musings.

MERMAIDS AND OTHER FABULOUS CREATURES

Mermaids were nothing new to Slessor. In fact, they were part of his program “to help heal the hurt of Gallipoli” (Jaffa 1971, 15):

Published shortly after World War I, Slessor’s first poems, adorned with bare-breasted mermaids and nudes astride gamboling centaurs, “were read with a quickening delight as symbols of youth resurgent from the mire and the wreckage” (15 n.3, quoting Charles Higham).

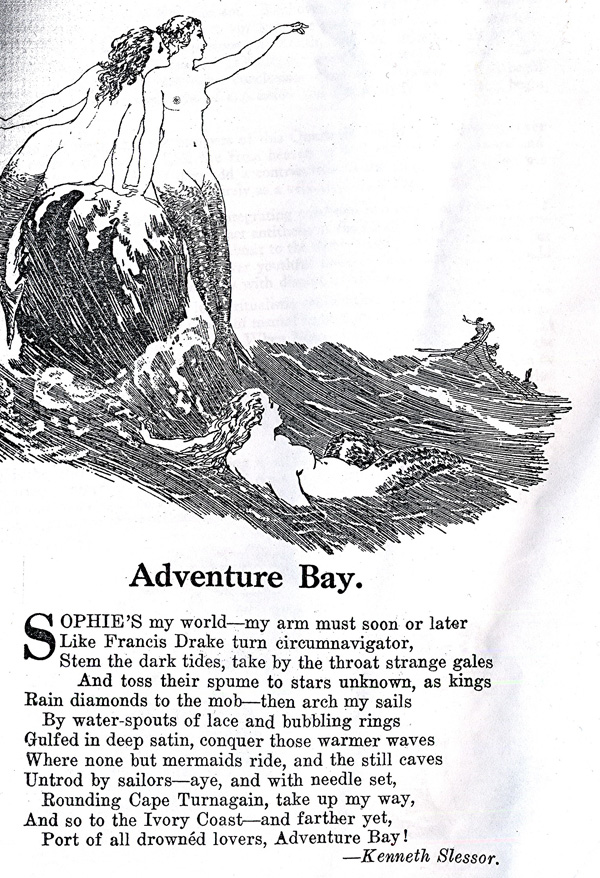

Slessor showcased mermaids in “Adventure Bay” and “Thieves’ Kitchen,” published in his first collection, Thief of the Moon (Slessor and Lindsay 1924). “Adventure Bay” had premiered a year previously: in the third issue of Vision, the mermaid was the iconographic theme, and the poem itself was accompanied by Norman Lindsay’s seductive engraving of mermaids hailing a lone vessel (Figure 2). There was even a quarterly called The Mermaid that attracted writers and artists like Slessor, Lindsay, and McCrae (NLA MS 3020, 2/1/8). And Slessor’s semi-fictitious character John Benbow sports a mermaid tattoo in “Metempsychosis,” a poem completed just before The Atlas (Slessor, Haskell, Dutton 1994, 102 and 384). So it’s no surprise that the mermaids’ “wet and scarlet lips” are the first of the poem’s words that Slessor composed, although he originally penned them for “Dutch Seacoast” (May 6, -s111; May 8, -s113; undated typed insert, -s178).8

Figure 2. Kenneth Slessor’s “Adventure Bay” in Vision: A Literary Quarterly (November 1923, 6). For its debut publication, “Adventure Bay” was illustrated with Norman Lindsay’s enticing mermaids. Although Slessor’s lover/narrator desires to “conquer those warmer waves/ where none but mermaids ride” (lines 7–8), Lindsay also alludes to Odysseus’s temptation by the Sirens in Odyssey 12. Reproduced from Vision: A Literary Quarterly.

Dolphins are also associated with eroticism, fantasy, and exploration in Slessor’s early poems “The Buccaneers” (1919), “The Embarkation for Cythera” (1924), and “Realities” (1924).9 In his journal, Slessor imagined that a sailor, spying a mermaid at night, “might … think no more of it than seeing a dolphin leap” (June 1, -s137). As for Ondines—French for “undines,” sea nymphs named for the “waves” (Latin undae) they supposedly inhabited—Slessor emphasized their wealth and sexuality in his poem “Undine” (Slessor, Haskell, Dutton 1994, 6), published in Thief of the Moon (Slessor and Lindsay 1924), and later anthologized with “Mermaids” in The Sea Poems of Kenneth Slessor (Slessor et al. 1990, 9). And he’d compared the laughter of undines to “bells in water” in his “The Embarkation for Cythera,” also in Thief of the Moon (Slessor and Lindsay 1924, 29). The Atlas drafts show Slessor giving Ondines the same “wet and scarlet lips” that his mermaids would have in the published version (-s150, insert between June 15 and 16; see also June 7, -s143).

Other characters seem new to Slessor’s work. Sirens were originally bird-women in Classical art (Neils 1995). But they had long since transformed into mermaids called “Syrens” who, like their Homeric counterparts (Odyssey 12.39–54, 165–200), lured sailors to destruction with their seductive songs (Benwell and Waugh 1965, 228; Ellis 1994, 41, 46‑47; Leclercq-Marx 1997; Ciobanu 2006, 11). Columbus—who reported that the New World contained no monstrous races only savages (Friedman 1981, 198–207, 257–258)—named the manatees of the Caribbean “sirens,” and scientists still classify these herbivores and their relatives as “Sirenia” (Ellis 1994, 88). Slessor’s “well-known and respected Harpies” were originally wind spirits called “Snatchers” (Gk Harpuiai: Odyssey 20.77), though they devolved into predatory women with wings and talons who left their stench behind after carrying off food or people (Apollonius of Rhodes, Argonautica 2.187–300; Vergil, Aeneid 3.210ff.). In stanzas six and seven, Slessor conflates the repellant Harpies with Sirens, who by tradition were able not only to fly but also, unlike the Harpies, to “sing” and “fork their foaming lily-fins below the side.” Finally, Slessor drew from sources other than Classical myth. His “seas … full of … flying Jinns” (stanza 4) refers to “genies” or “jinni,” Islamic spirits—familiar from The Arabian Nights—who assume human or animal form to aid, or harm, men. Germanic myths inform his lines: “Then from his cloudy stall, you heard the Kraken call,/ And, mad with twisting flame, the Firedrake roar” (stanza 1; see June 4, -s140, and June 19, -s157, respectively). The “Firedrake” or “fire-dragon” entered English literature in the Anglo-Saxon epic Beowulf, while “Kraken,” a Norwegian name, can refer to a sea-serpent sporting a horse’s head and a body spiraling over a mile-and-a-half (Ellis 1994, 45, 125).10 Memorialized in a sonnet by Tennyson11 and identified by “scientists now” as a giant squid Architeuthis (Ellis 1994, 113–164, 365), its undulations were said to resemble islands, and its coils to crush ships (ibid., 125, 143; Encyclopedia Britannica 1911, 15:923, s.v. “Kraken”). Slessor’s “murky stall” is the perfect home for a horse-headed creature, though the Kraken’s “call” may derive from Jules Verne’s description in Twenty-Thousand Leagues under the Sea (1870) of the giant squid’s beak-like mouth (Ellis 1994, 115, 118).

In Slessor’s poetry journal, the Kraken first surfaces in a list of sea creatures: “Mermaids, Dolphins, Krakens, Dragons, Chilons, Balena, Hippocampus, [?], Monk fish, Bishop-fish/ Calamary, Cetacean” (June 4, -s140). Slessor must have consulted the landmark 11th edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica for “Doctor Gerbrandus’s Mermaids,” since his “July 9” entry (‑s175) cites “D’Arras/ John Gerbrandus a Leydis [Leiden]”—two names found in that encyclopedia’s entry “Mermaids and Mermen.”12 And Slessor certainly had access to Captain Bayldon’s library, which specialized in books on discovery and exploration, like Philip Alexander’s The Earliest Voyages Round the World, 1519–1617 (1916), with its Theodor de Bry illustration of Magellan sailing through the Strait that bears his name and into an ocean filled with mermaids and sea-monsters (Figure 3). Bayldon also collected books on the romance of the sea, including Legends and Superstitions of the Sea and of Sailors, with its chapters on mermaids, water-sprites, and sea-monsters (Bassett [1885] 1971); and Monsters of the Sea: Legendary and Authentic (Gibson 1890), which dealt with the legendary Kraken. In fact, both the Kraken and the Firedrake make their appearance in Cuckooz Contrey in poems closely associated with The Atlas and completed only a short time before; namely, “Captain Dobbin” and “Five Visions of Captain Cook.” The eponymous hero of “Captain Dobbin” watches “the lights, like a great fiery snake, of the Comorin/ Going to sea” (Slessor, Haskell, Dutton 1994, 77, 362), while “Five Visions of Captain Cook” opens with “Cook was a captain of the Admiralty/ When sea-captains had the evil eye,/ Or should have, what with beating krakens off” (87, 366). The lines from “Five Visions” stand out because Slessor originally experimented with “Evil Eye” in the fifth stanza of “Mermaids” before settling on “the old Skeleton”—presumably the sea “full of swept bones”: “Then mariners …/ Dicing against the Evil Eye afresh/ In caravels no bigger than their faces” (June 24, -s162). If Slessor exchanged lines within The Atlas poems, the sea-obsessed sequences of Cuckooz Contrey reveal their own interminglings.

Figure 3. “Inventio Maris Magallanici” (Discovery of the Sea of Magallanica), plate 15 in America, part 4 of Theodor de Bry’s Les Grands Voyages (Bry and Benzoni 1594). If neither title or caption, nor the text of chapter 15 (pp. 66–67) refers to the mythical characters in this copper-engraving, that’s because De Bry took the image, drawn by Jean Stradan and engraved by Jean Galle, from a 1522 work celebrating the return of Magellan’s flagship Victoria after the first circumnavigation of the globe (Bucher 1981, 25–26). Like this famous illustration, Slessor’s poem features mermaids, sea-monsters, exotic savages, and a nonchalant “mariner” aboard his “brig.” There is also a “flying” spirit (a Jinn rather than Apollo) as well as “flames” (for the Firedrake rather than Tierra del Fuego), peculiar natives, and a predatory bird-like creature (a Harpy, rather than a Roc, who isn’t carrying off an elephant—an animal found in “Antient Africa” rather than in Patagonia). While no direct evidence exists of Slessor’s having seen this triumphal image in Balydon’s library or elsewhere, the Captain’s Remarks on Navigators of the Pacific, from Magellan to Cook came out the same year as Cuckooz Contrey (Bayldon 1932). Reproduced from Philip Alexander’s The Earliest Voyages Round the World, 1519–1617 (1916, 25).

PORING OVER OLD MAPS OF THE WORLD

“Mermaids” may celebrate fanciful creatures, but maps are equally its subject. Besides the epigraph, two of the poem’s nine stanzas call attention to them. In stanza five “sailors … star[e] from maps in sweet and poisoned places.” And stanza three, added belatedly after Slessor had worked his way through the original five (June 30, -s168; July 3–4, -s170–171; July 6,-s173), focuses entirely on a type of map named only this once in The Atlas:

Then portulano maps were scrolled

With compass-roses, green and gold,

That fired the stiff old Needle with their dyes

And wagged their petals over parchment skies.

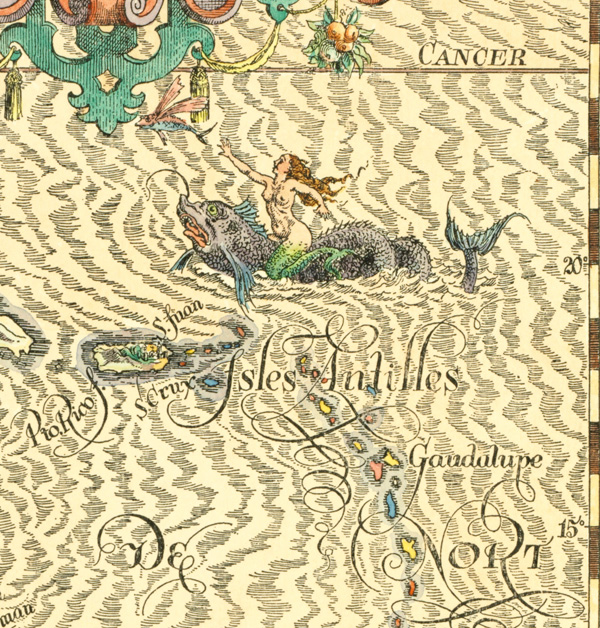

Variously called “portolanos” or “portolan/portulan” maps or charts, Slessor’s “portulano maps” refer to sea charts dating from around 1200 through the seventeenth century (see Francis Edwards 1929, 6, 91; Philip Lee Phillips Society 2010). Portolanos were originally designed as navigational tools rather than for contemplation (like medieval Christian mappaemundi, “world maps”) or for arm-chair exploration (like multi-volume atlases). Focused initially on the Mediterranean and Black Sea, portolan charts display compass roses intersecting networks of rhumb lines (see Figure 13, below), which when plotted with a compass, aided navigators in determining the direction and distance from harbor to harbor. Whether on vellum or another type of parchment, portolan charts are immediately recognizable by the accuracy of their coastlines, the proliferation of towns and place-names along the water, the paucity of geographical detail in the interior, and the absence of terrae incognitae. Old Maps of the World lists and describes in detail three portolanos, each an expensive seventeenth-century manuscript map on vellum (Francis Edwards 1929, 91, item 313; 108–109, item 515; 114–115, item 556). Slessor was clearly impressed. On the fifth page of his Atlas drafts, he put an “X” beside “portolanos/—portolan maps/ with/ compasses/ direction stars/ towns, trees and animals/ by Franciscus Oliva” (March 2, -s62). These words come directly from item 313, the “highly decorated” 1613 “Portolan Map of the Mediterranean with the adjacent coasts of Europe, Asia and Africa” (Francis Edwards 1929, 91). Some of the words he copied into his journal—“portolan maps (portolanos)/ compasses”—would reappear in his pivotal entry of “May 29” (-s134). But Slessor’s “compass-roses, green and gold” comes from item 556: Joël Gascoÿne’s “brilliant portolan or navigation chart in gold and colours with elaborate compass roses and other decorations, the whole most delicately drawn and coloured in reds, greens and yellows” (Francis Edwards 1929, 114). The sixth page of Slessor’s Atlas drafts records this discovery in his slightly embroidered “compass roses (spreading their green & yellow petals)” (“Atlas 6”: March 4, -s63). And he repeats the phrase in his “May 29” entry (-s134).

The epigraph of “Mermaids” does not come from a portolan chart, however. What the Francis Edwards catalogue emphasizes about the portolans is their historical importance as well as their accuracy and reliability, qualities more attractive to a mariner than to Slessor. Nevertheless, if he was looking for more imaginative items in Old Maps of the World, no poem in The Atlas offered him more hope for finding a suitable opening quote, even if we exclude the titles Slessor had contemplated as epigraphs for “Lost Lands” and then listed along with their item numbers (March 27–28, -s82 to -s83).13 For instance, on the third page of the Atlas drafts, he’d placed a large “X” beside “Italian Map with / galleons, caravels, sloops,/ flying fish, sea monsters/ battles and mermaids” (“Atlas 3”: February 26, -s60; see Dutton 1991, 146). The first mention of mermaids in Slessor’s journal, the quote belongs to a beautifully ornamented atlas of Italy by Giovanni Antonio Magini (1555–1617) (item 100: Francis Edwards 1929, 46). In Magini’s 1620 work, Slessor seemed to have all that he wanted: colorful sea-creatures to accompany his mermaids, a seventeenth-century date (unlike the maps listed for “Lost Lands”), and an Italian title to complement the English and Dutch titles he’d chosen for his other epigraphs14 (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Giovanni Antonio Magini’s Regno di Napoli, pl. 48 in his atlas Italia, engraved by Benjamin Wright and published posthumously by Magini’s son Fabio (Bologna, 1620: 38 × 44 cm, 15 × 17 ¼ inches). Of the maps in Magini’s atlas that feature mermaids, this is the most ornate, displaying not only a mermaid and a piping merman in the sea, but also ships, sea-monsters, and a cupid merman on the cartouche. Regno di Napoli is not among the Magini maps listed separately for six shillings in Old Maps of the World (Francis Edwards 1929, 89, entry 301). Reproduced from Enciclopedia Bompiani, vol. 6 (Storia), Gruppo Editoriale Fabbri, Bompiani, Sonzogno, etas; Milan 1988. Posted on Wikimedia Commons and accessed March 26, 2015: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kingdom_of_Naples.png.

Slessor’s allusion to the Magini atlas so early in The Atlas drafts suggests that its catalogue description inspired not only the title “Mermaids,” but perhaps even Slessor’s decision to imitate in verse those early maps that populate exotic geographies with mythical hybrids and monsters. For immediately below this “Italian map” quote,15 Slessor copied details from three more items in the Francis Edwards catalogue (“Atlas 3”: February 26, -s60; bracketed details from Old Maps of the World are my own):

giants with puffed cheeks symbolising winds [Ptolemy’s atlas: item 534, p. 110]

Virginia & Florida map with/ ships, seamonsters [sic], natives & animals/ gilded ships gleaming in water [Mercator-Hondius atlas: item 105, p. 47]

X figures of anthropophagi [Mercator atlas, map of Brasil by Hondius: 1633, item 106, p. 49]

With “Anthropophagi (in Brasil)” checked again below them, the first two items would resurface in Slessor’s pivotal “May 29” entry, where “Lost Lands” transitions into “Mermaids.” There they merge with a list of words from his “Atlas 5” entry (March 2, -s62: opposite “portolanos”). The heavy bracket enclosing them in his “May 29” entry emphasizes their importance to Slessor (‑s134; below, internal brackets from Old Maps of the World are my own):

galleons, caravels, sloops, flying-fish, sea-monsters, mermaids [Magini map, 1620: item 100, p. 46],

giants as winds with puffed cheeks [Ptolemy’s atlas, 1542: item 534, p. 110],

buccaneers [Sanson Archipelague du Mexique, 1692: item 657, p. 125],

elephants [G. Blaeu, Aethiopia Superior vel Interior, 1662: item 442, p. 102],

gilded ships, in water, natives of Virginia & Florida [Mercator-Hondius atlas, 1613: item 105, p. 47],

ostriches, monkeys [G. Blaeu, Aethiopia Superior vel Interior, 1662: item 442, p. 102],

dolphins [P.J. Sauermann’s map, 1699: item 606, p. 121],

palanquins [no map identified],

Negroes [G. Blaeu, Aethopia (sic) Inferior, vel Exterior, 1640: item 494, p. 107].

Again, Slessor used none of these titles. He already had a Blaeu epigraph, even though the epigraph for “Dutch Seacoast” came from an atlas by Joan Blaeu rather than his father Willem Janszoon Blaeu (“G. Blaeu” representing the Latin form “Guilelmus Blaeu”). And Slessor had a map of Africa in Robert Norton’s “Platt of Argier.” Perhaps “Virginia and Florida” didn’t sound exotic enough, a problem the Mercator-Hondius map shared with Magini’s “Italia”; and both were limited geographically. The Italian atlas had a more insurmountable problem: its single-word title. (Ultimately, despite his depictions of sea battles, Magini also lost out to the “Sanson” epigraph in the final poem of The Atlas, “The Seafight” [August 11, -s208].) In his “July 2” entry with its header “O Mermaids” (-s169), Slessor subsequently played with the title of the Mercator-Hondius atlas containing the map of Virginia and Florida: “L’Atlas ou Méditations Cosmographique de la Fabrique du Monde, et figure di celuy, de nouveau revenue et augmenté, Amsterdam, J. Hondius, 1613.” But he later crossed out the name of this very important atlas, leaving an equally evocative title below it (July 2, -s169):

A New and Accurat Map of the World, in two Hemispheres, Western and Eastern, with the Heavens and Elements, a Figure of the Spheare, the Eclipse of the Sunne, the Eclipse of the Moon.”—J. Speed, 1676.

Slessor had finally chosen his epigraph.

But why this one? By his “July 2” entry, it is clear that Slessor wanted to introduce “Mermaids” with the title of a seventeenth-century world map ornamented with ships and sea-creatures. The Mercator-Hondius atlas had “La Fabrique du Monde” in its title, and a world map among its offerings. Unfortunately, the Francis Edwards catalogue offers too early a date for the map and says absolutely nothing about its ornaments: “THE WORLD according to Mercator 1587, consisting of two spheres within a very fine arabesque border” is all that there is (Francis Edwards 1929, 47). Nevertheless, when Slessor eliminated the Mercator-Hondius atlas, he replaced it with something he’d been considering nearly as long.

JOHN SPEED

Speed’s map was already known to Slessor, even though he didn’t record the name “J. Speed” until he’d almost finished “Mermaids” (July 2, -s169; NLA MS 3020/19/7). On the sixth page of his Atlas drafts, Slessor had checked “the Eclipse of the Sunne” (March 4, -s63), then transferred the phrase to his pivotal “May 29” entry, where it appears immediately after “portolan maps (portolans)/ compasses” (-s134). Later, while choosing his epigraph for “Mermaids,” he would have been reassured of Speed’s credentials: the cartographic-landmarks section of the Francis Edwards catalogue entitled “Data” highlights the year 1611 when “John Speed published the second [English] county atlas” following Christopher Saxton’s The Counties of England and Wales in 1579 (Francis Edwards 1929, 7, 61–63). Nearly twenty items advertised in the catalogue bear Speed’s name.16 And nearly sixty of his county maps of Great Britain and Ireland are listed in item 173, which also informs us that “John Speed, 1552–1629, was born at Farndon in Cheshire” (ibid., p. 75). Further research reveals that Speed, the son of a Merchant Taylor, began his working-life as a tailor. Freed by patrimony from the Company (1580: Bendall 2004, 51:771), he began pursuing his interests in theology, history and cartography. By 1595, he’d produced a wall map of Canaan, his first cartographic endeavor; and three years later, presented maps to Queen Elizabeth. Under the patronage of Sir Fulke Greville, Speed secured an allowance and a sinecure appointment with the Customs Service (1598), thus releasing him “from the daily imploiments of a manuall trade” (quoted in Pollard 1898, 53:318; Skelton 1966, vii; Tooley 1977, 4; Barber 2007, 1636). In 1600, Speed donated three maps to the Merchant Taylor’s Company, who extolled his “very rare and ingenious capacitie in drawing and setting forth of mappes and genealogies and other very excellent inventions” (quoted in Baynton Williams 1991, vi). Speed made the acquaintance of the greatest intellects of his time, including Sir Robert Cotton, famous for his collection of manuscripts and maps.17 Speed is best known for The Theatre of the Empire of Great Britaine (Speed et al. [1611] 1612), “a highly individual work” containing his much-collected county maps and “clearly evok[ing his] personality as a scholar and writer” (Skelton 1966, vii). His name is also associated with the 1627 Prospect of the Most Famous Parts of the World (Figure 5)—“the earliest world atlas to bear the name of an Englishman” (ibid., v).18 Its opening map is A New and Accurat Map of the World—dated 1626, a year earlier than The Prospect. The 1626 map is essentially identical to the 1676 map, whose date Slessor copied from the Francis Edwards catalogue (Francis Edwards 1929, 111) into his own “July 2” journal entry (-s169: see above). Only the map’s imprint and title date distinguish the 1626 state from the 1676 state. Which means that although every published version of “Mermaids” contains “1675” in its epigraph, the date is clearly a misprint.19 The important year was 1676, for not only was The Prospect part of a combined edition, but The Theatre … with the Prospect (Speed 1676a, Speed and Baynton-Williams [1676] 1991) has been called “the best printed edition of the two works” (Skelton 1966, xii). By then, Speed had been dead for nearly half a century, and his New and Accurat Map of the World had been re-engraved “1651.” Through its final state in 1676, “1651” remained on the map hailed as “one of the best known and most important of English world maps” (Jonathan Potter Ltd. n.d.; see Shirley 2001, 341).

![Figure 5. Portrait of John Speed, copperplate engraving by Solomon Savery (ca. 1631–1632: 30.6 × 19.6 cm, 12 in. × 7 3/4 in.). This portrait, published by George Humble soon after Speed’s death in 1629 at the age of seventy-seven, was the frontispiece for the 1631–1632 edition of A Prospect of the Most Famous Parts of the World … Together with All the Prouinces, Counties, and Shires, Contained in That Large Theator of Great Brittaines Empire (Speed, Goos, and Gryp, 1631[–1632]). Image from Early English Books Online: Text Creation Partnership (EEBO-TCP) and accessed at the NYPL-Research Library, July 9, 2014.](https://cartographicperspectives.org/index.php/journal/article/download/cp79-haft/1377/6443?inline=1)

Figure 5. Portrait of John Speed, copperplate engraving by Solomon Savery (ca. 1631–1632: 30.6 × 19.6 cm, 12 in. × 7 3/4 in.). This portrait, published by George Humble soon after Speed’s death in 1629 at the age of seventy-seven, was the frontispiece for the 1631–1632 edition of A Prospect of the Most Famous Parts of the World … Together with All the Prouinces, Counties, and Shires, Contained in That Large Theator of Great Brittaines Empire (Speed, Goos, and Gryp, 1631[–1632]). Image from Early English Books Online: Text Creation Partnership (EEBO-TCP) and accessed at the NYPL-Research Library, July 9, 2014.

No matter what date appears on the world map, however, its title is always the same:

A New and Accurat Map of the World Drawne according to ye [the] truest Descriptions latest Discoveries & best Observations yt [sic] have beene made by English or Strangers.

Comparing this title to the epigraph of “Mermaids,” we notice that Slessor uses only its opening words before proceeding to describe the map itself:

“A new and Accurat Map of the World, in two Hemispheres, Western and Eastern, with the Heavens and Elements, a Figure of the Spheare, the Eclipse of the Sunne, the Eclipse of the Moon.”

This description certainly corresponds to the map’s content (Figure 6). With the double-hemisphere design so popular in the seventeenth century, it displays “two hemispheres, Western and Eastern,” although no text on the map identifies them as such. “The Heavens and Elements” is a phrase found on an inset at the top-left corner of the map. Furthermore, tucked between the earthly hemispheres, are two smaller celestial ones representing “The Heavens,” with “The Northern Hemisphaere” above “The South Hemisphaere.” The Elements, symbolized by naked gods, bracket these star charts. To the left of the northern celestial hemisphere, personified Water pours liquid into a stream; to the right, Earth holds her cornucopia. To the left of the southern celestial hemisphere, Fire tramples a fiery lizard; to the right, birds surround Aire. “A Figure of the Spheare” refers to the top-right inset and the words “A Figure to prove the sphearical roundnes of the sea” [sic]. The bottom-left inset is labeled “The Eclipse of the Sunne,” while the bottom-right inset features “The Eclipse of the Moone.”

Figure 6. John Speed, A New and Accurat Map of the World Drawne according to ye truest Descriptions latest Discoveries & best Observations yt have beene made by English or Strangers (1651/1676). This hand-colored engraving measures 15 × 20 ½ inches (38 × 51 cm), according to Old Maps of the World (Francis Edwards 1929, 111); and appears on a sheet 17 × 22 inches (43 × 56 cm), with each hemisphere 9 ¾ inches (25 cm) in diameter. Accompanying text entitled “The General Description of the World” appears on the verso. That the map was published for the 1676 folio edition of The Theatre … with the Prospect is apparent from the imprint “Are to be sold by Tho: Basset in Fleet Street and Ric: Chiswell in St. Pauls Churchyard” (at the feet of the map’s allegorical figure “Aire”: bottom, right of middle). This beautiful baroque map, perhaps originally engraved by Abraham Goos (Skelton 1966, vii), attempts to be up-to-date and scientific even as it symbolizes the transition between pre-modern and early-modern views, and between mythical and scientific conceptions of space. Courtesy of the State Library of New South Wales (SAFE/M2 100/1651/1), Sydney, Australia.

Why, given the map’s many details, did Slessor pick these for his epigraph? For the same reason he chose all of his epigraphs: he copied each directly from Old Maps of the World rather than from the map itself. As usual, Slessor is selective about what he takes. For instance, Slessor refers to “ships at sea” and “sea monsters” in his Author’s Notes to Cuckooz Contrey (Slessor 1932, 77), yet for his poem he preferred to craft word-pictures like “brigs no bigger than their moon-bunched faces” rather than to copy the catalogue’s words “numerous ships and sea monsters” into his own epigraph. (He omitted “sea monsters” and crossed off “numerous ships” in his July 2, -s169 entry.) Below, I’ve inserted brackets around details in item 538 that Slessor chose not to incorporate into his epigraph or the body of his poem (Figure 7):

538 SPEED (J.)

A New and Accurat Map of the World, in two Hemispheres, Western and Eastern, [numerous ships and sea monsters; in the corners are] with the Heavens and Elements, a Figure of the Spheare, the Eclipse of the Sunne, the Eclipse of the Moon [with portraits of Drake, Magellan, Van de Noort and Candish, 20 ½ by 15 ins.], 1676 [£4].

[A hypothetical coast-line is given for the N.E. coast of Australia, “These Coasts were first discovered by a Spainsh Ship separated from her fleet, and driven heere along in ye Southerne Sea.” California is shown as an island, and the coast northwards stretches abruptly away westwards into the Pacific.]

![Figure 7. Description of John Speed’s A New and Accurat Map of the World, item 538 in the Francis Edwards catalogue Old Maps of the World, or Ancient Geography; a Catalogue of Atlases & Maps of All Parts of the World from XV Century to Present Day (London: F. Edwards Ltd., 1929, 111). The map’s description appears on the last of the four pages comprising “American and General Maps of the World” (108–111), which is contained in Part II, “Single Sheet Maps or Maps of One or More Sheets on Particular Districts” (71–138)—the longest of the catalogue’s three parts and the one advertising Speed’s maps. The third of four catalogues in the short-lived “new series” of 1929, Old Maps of the World and its companion booklets were larger and far better illustrated than the more than 500 Francis Edwards catalogues preceding it. Courtesy of the New York Public Library (Map Div. [Edwards, F. Ancient geography]) and of Francis Edwards Ltd.](https://cartographicperspectives.org/index.php/journal/article/download/cp79-haft/1377/6445?inline=1)

Figure 7. Description of John Speed’s A New and Accurat Map of the World, item 538 in the Francis Edwards catalogue Old Maps of the World, or Ancient Geography; a Catalogue of Atlases & Maps of All Parts of the World from XV Century to Present Day (London: F. Edwards Ltd., 1929, 111). The map’s description appears on the last of the four pages comprising “American and General Maps of the World” (108–111), which is contained in Part II, “Single Sheet Maps or Maps of One or More Sheets on Particular Districts” (71–138)—the longest of the catalogue’s three parts and the one advertising Speed’s maps. The third of four catalogues in the short-lived “new series” of 1929, Old Maps of the World and its companion booklets were larger and far better illustrated than the more than 500 Francis Edwards catalogues preceding it. Courtesy of the New York Public Library (Map Div. [Edwards, F. Ancient geography]) and of Francis Edwards Ltd.

Slessor names none of the four circumnavigators whose portraits flank the terrestrial hemispheres; namely, the Englishmen celebrated elsewhere on the map—Sir Fra[u]ncis Drake (1577–1580, top left) and Thomas Cavendish (“Mr. Thomas Candish”: 1586–1588, top right)20—as well as the Portuguese nobleman Ferdinand[us] Magellan[us] (1519–1522, lower left), who died in 1521 after “discovering” the Magellan Strait; and the Dutchman Oliver[us] van der Noort (1598–1601, lower right) (see Alexander 1916, xii–xxiii). Yet in the first stanza alone, “Firedrake” plays off Drake’s name,21 while “Conquistador,” alludes not only to Magellan, who sailed for Spain, but also to Magellan’s Spanish contemporaries, Cortez (1519) and Pizarro (1531), “conquerors” of Mexico and Peru, respectively.22 In his poem, Slessor appears equally unconcerned about the map’s geographical eccentricities, although map dealers and cartographic historians repeatedly advertise its depictions of California as an island and North America’s bulging West Coast. Yet immediately after choosing the Speed map for his epigraph, Slessor added two words to his poetry journal—“Southerne Sea”—clear evidence that the name was crucial to his final choice (July 2, -s169).

Because of Slessor’s reliance on the Francis Edwards catalogue, the same question inevitably arises for each of his Atlas poems: could his choice have resulted from perusing the Speed map itself, rather than relying solely on the catalogue’s description of the map? Probably not. To begin with, The Prospect and its maps are relatively rare outside of Britain (Shirley 2001, 341, entry 317). Unless Slessor had access to a private copy of the atlas or to a rare facsimile of the world map, therefore, chances are that he never saw the map while composing “Mermaids.” Then there’s the fact that half of item 538 is devoted to the Southerne Sea and the “hypothetical coast-line … for the N.E. coast of Australia.” The map, by contrast, refers only obliquely to “Southerne Sea.” Readers must first locate the cartouche just above the enormous landmass called “Magallanica” at the southern tip of the western hemisphere. Only then, to the left of that cartouche, does the legend quoted in the Francis Edwards catalogue come into view: “these Coasts were first discovered by a Spainsh [sic] Ship separated from her fleet, and driven heere along in ye Southerne Sea.”23 It’s true that “Mar del Zur”—Spanish for “Sea of the South”—looms large on the map’s western hemisphere, the words extending along the west coast of the Americas from present-day California to Peru. Yet despite its prominence on the map, the name “Mar del Zur” appears nowhere in The Atlas drafts. And this, even though Slessor’s journal attests to his faithful copying of the Francis Edwards catalogue, including many Spanish toponyms (e.g., February 22, -s58, from item 38, p. 28; February 28, -s61; and March 6, s65, -s132, from item 133, p. 58, and item 135, p. 59). But what if Slessor had a copy or facsimile of the Speed map? If Magallanica’s interior is not colored in, the catalogue’s connections between “these Coasts” and “the N.E. coast of Australia”—or, for that matter, between either of those coasts and the “Southerne Sea”—are anything but clear (Figure 8). The “hypothetical coast-line” is almost impossible to make out; and not only does the legend lie significantly east of modern-day Australia, but also just west of the name “The Pacificke Sea” on the map. Even when that coastline is outlined in color and its boundaries filled in, as in Figure 6, the double-hemisphere design still separates Magallanica, in the western hemisphere, from The Southerne Unknowne Land, located at the southern tip of the eastern hemisphere and also below “The Indian Sea.” Even if the viewer assumes that Magallanica and the Southerne Unknowne Land are two regions of a single land, rather than two different lands,24 the northwest coast of Magallanica plunges seven degrees below the northeastern coast of the Southerne Unknowne Land at the map’s margins. Is this a draftsman’s error? Or another uncertain certainty reflecting the millennia-old philosophical mindset—championed even by the great Mercator (National Library of Australia 2013, 90)—that the hypothetical super-continent Terra Australis Incognita had to exist in order to balance the earth’s other lands? Or a hint, as the catalogue suggests, at the “strong northern projection” of northeastern Australia (see Tooley 1979, viii)? Even with an aid like Figure 6, in other words, the relationship between “Southerne Sea” and northeastern Australia doesn’t leap off the map. For Slessor, Old Maps of the World remains the most likely source for the entire content of the Speed map.

Figure 8. John Speed, A New and Accurat Map of the World Drawne according to ye truest Descriptions latest Discoveries & best Observations yt have beene made by English or Strangers (1651/1676). Unlike Figure 6, this hand-colored original shows only the vague outlines of Terra Australis Incognita, portrayed as Magallanica and the Southerne Unknowne Land. Courtesy of the Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations (Map Division 02-321).

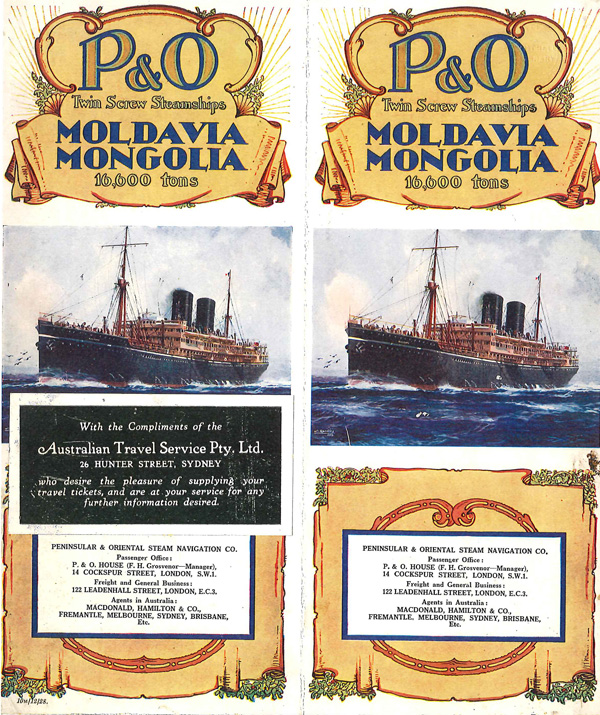

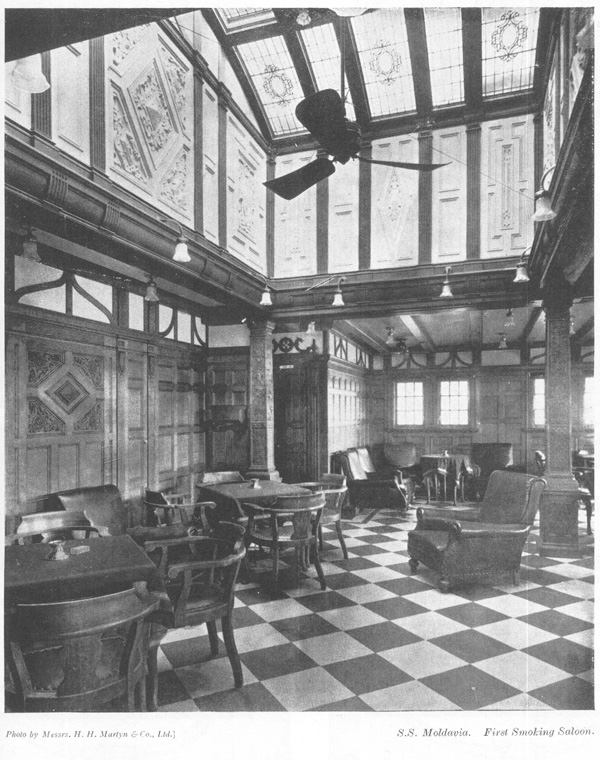

Like the other poems of The Atlas, “Mermaids” mentions neither the Southerne Sea nor Australia. But it does name the Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Company, otherwise known as “the P. & O.” (stanza 6; see June 12, -s147ff.). London-based to this day, the P&O markets itself as the first cruise line (Howarth, Howarth, Rabson 1994, 47, 107). What is significant for the fourth poem of The Atlas, however, is that the P&O began opening routes to Australia in the mid-nineteenth century, and continued its passenger service throughout Slessor’s lifetime (ibid., 83–85, 155; Rabson and O’Donoghue 1988, 17, 358). To publicize its routes the company produced illustrated brochures, including one advertising the SS Moldavia and the SS Mongolia, two P&O steamships built after World War I for passengers and cargo en route between England and Australia. A copy of this 1928 brochure, distributed by the Australia Travel Service in Sydney, found its way into Captain Bayldon’s nautical library, where it remains to this day (Figure 9). And presumably into Slessor’s hands, for the brochure features a photograph of the SS Moldavia’s First Saloon (Figure 10). This image may have inspired his lines about the Harpies—“Nor do they tumble in the sponges of the moon/ For the benefit of tourists in the First Saloon” (see also June 29, -s167). If so, the P&O advertisement is the second piece of inspirational ephemera that Slessor could have found at Captain Bayldon’s.

Figure 9. P&O Brochure advertising “Twin Crew Steamships Moldavia Mongolia 16,600 tons.” First of twelve pages, to which is stapled a card with the address and compliments of the Australian Travel Service Pty. Ltd. The brochure in the Babylon Nautical Collection is in an uncatalogued folder, supposedly containing items from the 1930s and 1940s. The brochure and its illustrations itself can be dated more precisely, however, for “10M/12/28” appears on the cover’s lower left. In the Australian/British dating standard, that’s December 10, 1928, the “M” probably being “Monday,” the day on which the 10th of December fell that year (Wendy Holz, email to author, August 14, 2014). What this means is that the brochure was available to Slessor while he was composing “Mermaids.” As for the vessels themselves, the Moldavia and Mongolia were constructed in 1922 and 1923, respectively, the ships after which they were named having been sunk in World War I (Swiggum and Kohli 2008). P&O Twin Screw Steamships: Moldavia Mongolia, brochure in Francis J. Bayldon papers, MLMSS 160/Box 12, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales.

Figure 10. “S.S. Moldavia, First Smoking Saloon,” photographed by Messrs. H. H. Martyn & Co., Ltd. From a 1928 P & O brochure advertising “Twin Screw Steamships: Moldavia and Mongolia” and distributed “with the compliments of the Australian Travel Service Pty. Ltd., 26 Hunter Street, Sydney.” The ships accommodated around 230 1st class patrons (Rabson and O’Donoghue 1988, 172, 189–190), who paid “£100 Single, £175 Double” for a return ticket between Australia and London, according to The Sydney Morning Herald, December 6, 1930 (“Advertising” 1930). As the 1926 “P&O Pocket Book” boasted (Rabson and O’Donoghue 1988, 172):

“Everyone…likes to journey in luxury when luxury is possible. And all men like the company of the ‘people who matter’… so it comes that there is nothing in the life of the average man half so full of interest or so much enjoyed as the six weeks of the longest P&O voyage—the run to Australia. Such a journey is the cream of human experience.”

P&O Twin Screw Steamships: Moldavia Mongolia, brochure in Francis J. Bayldon papers, MLMSS 160/Box 12, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales.

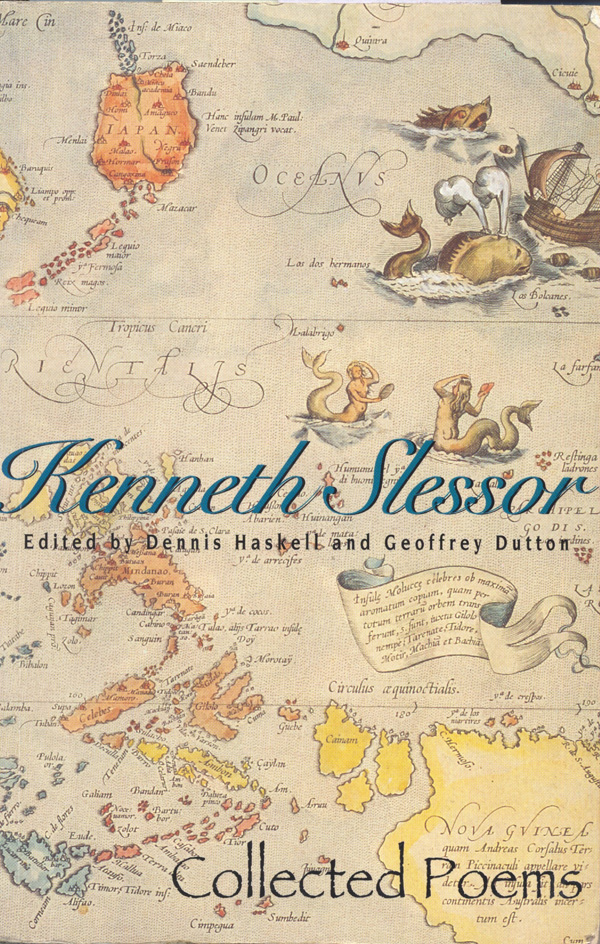

“The P. & O.” and its “First Saloon,” however oblique they may be, are Slessor’s only allusions in the entire Atlas to his native Australia. Its virtual absence ultimately derailed his ambitions for the sequence in favor of other gems in Cuckooz Contrey, like “Captain Dobbin” (April 1929) and “Five Visions of Captain Cook” (May 1929), both composed shortly before The Atlas (Slessor, Dutton, Haskell 1994, 362, 366). So much so that in his influential One Hundred Poems (1944) and Poems (1957), “Captain Dobbin”—whose mariner hero is modeled on Captain Bayldon (Kiernan 1977, 7)—abruptly replaced The Atlas as the opening work of Slessor’s middle period, and monopolized that position until the publication of the definitive Kenneth Slessor: Collected Poems, distributed under the HarperCollins imprint more than twenty years after Slessor’s death (Slessor, Haskell, Dutton 1994; see Haft 2011, 25, 33).

But what is most peculiar about Slessor’s choice of the Speed world map is the disparity between what the map actually depicts and what readers of “Mermaids” assume it depicts. Consider mermaids themselves. Nowhere are they to be found in the catalogue’s description of item 538. Nor do they appear anywhere on the map, not even decorating its cartouches or floating with other mythical creatures in its celestial hemispheres. Yet while sketching his “Notes” for The Atlas into the final “Mermaids” entry of his poetry journal, Slessor wrote: “Mermaids—Speed: map is filled with numerous ships at sea, mermaids and sea-monsters” (July 22, -s191: emphasis mine).25 And he said nearly the same thing in his Author’s Notes for Cuckooz Contrey: “‘MERMAIDS.’—Speed’s map is filled with pictures of ships at sea, mermaids and sea-monsters” (Slessor 1932, 77: emphasis mine). However, in the published notes, quotation marks have been inserted around “Speed’s map is filled with … mermaids … ” as if the assertion came from the same Francis Edwards catalogue that Slessor had just acknowledged as the source “for much of the information concerning the subjects of these poems” (ibid., note for The Atlas). Quotations also appear around the entire passage that constitutes Slessor’s note for “Dutch Seacoast.” But while “to see a Dutch town by Blaeu…” is a direct quote from Old Maps of the World (Francis Edwards 1929, 4–5), “Speed’s map is filled with … mermaids …” is not.

Was Slessor lying? Short of the quotes being a publisher’s addition (and one that the usually fastidious poet failed to correct), the answer is “absolutely.” Ships and sea-monsters commonly ornament Speed’s maps, including ours; two others—Asia and Jamaica—are also advertised as such in Old Maps of the World (item 330, p. 93; item 703, p. 129). Mermaids, however, are far more elusive. The Prospect of the Most Famous Parts of the World reveals not a single one, even though its maps sport birds and animals as well as ships and sea monsters. Speed’s Theatre of the Empire of Great Britain is another story. As early as 1604 or 1605, the famous Flemish engraver/mapmaker Jodocus Hondius Senior (1563–1612)—the same Hondius of the Mercator-Hondius atlas (1606)—began engraving maps for Speed’s Theatre (Skelton 1966, v, vii–viii; Baynton-Williams 1991, v–vi, viii), and these maps were incorporated into the combined 1676 edition of The Theatre of the Empire of Great Britain, with The Prospect. At least two mermaids can be glimpsed there along with the occasional unicorn, merman, bearded Triton, or Neptune riding a sea monster (Speed 1676a; Speed and Baynton-Williams [1676] 1991). One appears in the Irish Sea on The Countie Pallatine of Lancaster (between pages 75 and 76; see Speed and Hondius 1610), while another graces Merionethshire Described 1610 (Figure 11). Given that in the 1920s Francis Edwards was advertising The Theatre …, with The Prospect for between £5.50 (Tooley 1977, 8) and £60 (Francis Edwards 1926, 2, item 8), a copy may have been accessible to Slessor in Sydney. On the other hand, the Bayldon Collection doesn’t contain The Theatre (or The Prospect, or, for that matter, an independent copy of A New and Accurat Map of the World). And it is extremely unlikely that Slessor would have searched these maps out. For one thing, the Francis Edwards catalogue makes no mention of The Countie Pallatine of Lancaster; and although it does list a Lancashire map and the Merionethshire map, it details none of their decorations (Francis Edwards 1929, 75–76: item 173). Furthermore, Slessor himself was composing The Atlas while working full-time as a journalist for Smith’s Weekly. Had he seen these county maps, he could have easily written “Speed’s maps are filled with pictures of … mermaids” to keep his Author’s Notes as “accurate” as the title in his epigraph.

![Figure 11. A mermaid combing her locks on an inset map of Harlech Castle. Detail from John Speed’s Merionethshire Described 1610 (38.5 × 51cm, 15 × 20 inches), one of the Welsh county maps that appeared in his Theatre of the Empire of Great Britain from its earliest publication. This image comes from the rare 1616 Latin edition (Speed, Holland, and Camden, 1616); the 1676 edition of The Theatre … with the Prospect displays the map between pages 117 and 118 (Speed 1676a, Speed and Baynton-Williams [1676] 1991). Engraved by Jodocus Hondius Senior, who resided in England from 1583–1593, the full Merionethshire map also features compass roses as well as ships and sea monsters in the Irish Sea. Courtesy of Richard Nicholson, antiquemaps.com.](https://cartographicperspectives.org/index.php/journal/article/download/cp79-haft/1377/6449?inline=1)

Figure 11. A mermaid combing her locks on an inset map of Harlech Castle. Detail from John Speed’s Merionethshire Described 1610 (38.5 × 51cm, 15 × 20 inches), one of the Welsh county maps that appeared in his Theatre of the Empire of Great Britain from its earliest publication. This image comes from the rare 1616 Latin edition (Speed, Holland, and Camden, 1616); the 1676 edition of The Theatre … with the Prospect displays the map between pages 117 and 118 (Speed 1676a, Speed and Baynton-Williams [1676] 1991). Engraved by Jodocus Hondius Senior, who resided in England from 1583–1593, the full Merionethshire map also features compass roses as well as ships and sea monsters in the Irish Sea. Courtesy of Richard Nicholson, antiquemaps.com.

Nor are Speed’s mermaids the iconic preening-in-mirror type depicted on maps from the Middle Ages through the Renaissance (Benwell and Waugh 1965, 227 and pl. 11b). That’s one reason why Penny Maxwell turned to Abraham Ortelius (1527–1598), author of the “first modern atlas” (Francis Edwards 1929, 6; see 53), when designing the cover for the Angus&Robertson/HarperCollins edition Kenneth Slessor: Collected Poems (Figure 12). After Dennis Haskell requested that a map grace the cover of the collection,26 Maxwell chose Indiae Orientalis Insularumque Adiacientium Typus, originally plate 48 in Ortelius’s pioneering atlas, Theatrum Orbis Terrarum (Antverpiae: Coppenium Diesth, 1570), four editions of which were advertised in Old Maps of the World (Francis Edwards 1929, 52–53, items 119–122, £15 to £120). Housed in the National Library of Australia, Ortelius’s map of south-east Asia and the islands adjacent features sea-monsters, as large as Japan, attacking a ship, while in the Pacific below the Tropic of Cancer, two voluptuous mermaids brandish their mirrors.27 Maxwell’s charming cover goes a long way toward rectifying the absence of maps in Slessor’s poetry collections after 1932. For it to allude so directly to “Mermaids” means that The Atlas and its cartographic delights are highlighted as well in the definitive edition of Slessor’s poetry. Furthermore, Maxwell may have rejected, for reasons beyond their lack of accessibility, the maps whose titles constitute the epigraphs of the sequence. Like poems, maps are representations of “reality” infused with their own subjectivities and limitations: not one of the maps named in Slessor’s epigraphs manages to speak to the feeling, sensuality, or exotic nature of The Atlas sequence as a whole in the way that the Ortelius map does. Nor do they suggest the variety of strange lands and bygone eras that animate Slessor’s collected poetry. Nonetheless, because Ortelius’s map represents an earlier stage in the history of the atlas, it is no more “right” for “Mermaids” than the world map attributed to John Speed.28 In fact, Ortelius’s work was completely supplanted by the Mercator-Hondius atlas to which Slessor’s journal repeatedly refers (Feb 26, -s60; May 29, -s134; July 2, -s169; see Francis Edwards 1929, 47, item 105; Skelton and Humphreys [1926] 1952, 58). The only seventeenth-century cartographic work described in the Francis Edwards catalogue as featuring mermaids is the Magini atlas of Italy. And Slessor discarded Magini early in his composition.

Figure 12. Penny Maxwell’s cover design of the definitive Kenneth Slessor: Collected Poems, edited by Dennis Haskell and Geoffrey Dutton (Pymble, Sydney: Angus&Robertson, 1994). Maxwell chose the right side of Abraham Ortelius’s double-page Indiae Orientalis Insularumque Adiacientium Typus (1570 or 1571), a double-page map of Southeast Asia and the adjacent islands (32.5 × 47.5 cm, 12 ¾ × 18 ¾ inches). Framing the Tropic of Cancer (just above the collection’s title) are the temptations and threats that beset sailors: two mermaids and enormous sea-monsters attacking a ship. Their appearance in the Oceanus Orientalis accords with cartographic practice: since at least the 12th century, such creatures were thought to inhabit poorly explored waters of the “East,” particularly the Indian Ocean (Van Duzer 2013b, 19, 43–45, 47–48, 55–56, 68–69, 80–81) and, later, the Pacific (ibid., 96, 100, 105). The map that Maxwell used is housed in the National Library of Australia (MAP NK 5318). Her cover design is reproduced with permission of HarperCollins Publishers Australia Pty Limited.

By now you’ve realized that the Speed map displays neither Sirens nor Ondines, neither Harpies nor Jinns, neither Kraken nor Firedrake, neither Hermaphrodites nor Anthropophagi.29 Although Pliny’s influential Natural History—with its account of such mythic creatures—had been translated into English by Philemon Holland in 1601 (Ellis 1994, 51), Speed, like most intellectuals of his day, was no believer in them (Lowes [1927] 1964, 447 n. 34; Friedman 1981, 198). Centaurs and other hybrids might appear in his celestial hemispheres, but not in his terrestrial landscapes, no matter how unknown or unexplored. The “General Description of the World” on the map’s verso offers an enlightened interpretation of geographical advances: “Our God in these latter times hath enlarged our possessions, that his Gospel might be propagated, and hath discovered to us inhabitants, almost in every corner of the earth” (paragraph 20, in Speed and Skelton [1627] 1966, 2; and Speed and Baynton-Williams [1676] 1991, 139). Of those living in Magellanica [sic], the conjectural outlines of which extend below the tip of South America, the “General Description of the World” records that, however “little can be reported,” its inhabitants are merely “barbarous” and “goe naked”—a far cry from monstrous (paragraph 24). And in “The Southern Unknowne Land” stretching beneath the Indian Sea, the map’s cartouche simply states: “This South part of the world, containnyng almost the third part of the Globe, is yet unknowne certaine sea-coasts excepted, which rather shewe there is a land then discrye either Land, people, or Comodities.” All of which is to say that A New and Accurat Map of the World attempts to be scientific and up-to-date in its emphasis on global exploration, its profusion of ships plying the seas, and its plethora of names identifying far-off places.

Yet for us, the map is refreshingly old-fashioned, symbolizing the transition from pre-modern to early-modern views, and from mythical to scientific conceptions of space. Its diagram of the outmoded Ptolemaic universe centered on the earth, its picture of God’s arm holding an armillary sphere to demonstrate the “roundnes of the sea,” its distended boundaries of North America and enormous “Southerne Unknowne Land,” its accompanying “General Description of the World”—all seem like quaint attempts to reconcile contemporary discoveries with Biblical and Classical notions of geography.

Another problem remains, however: Speed’s name appears nowhere on the world map. Copyright issues might have led to reluctance on his part (Baynton-Williams 1991, viii), for there is no question that A New and Accurat Map of the World is indebted to a rare and identically named double-hemisphere map by his countryman William Grent (1625).30 That Speed was blind by the mid-1620s could have prevented him from being involved with the world map, which was one of only three maps not attributed to him in The Prospect. The inevitable conclusion is that the ascription of Speed’s name to the world map “must be considered spurious” (Skelton 1966, ix). Nor may Speed have had much to do with The Prospect, the 1627 premiere edition of which was the last one published in Speed’s lifetime. “Primarily a commercial venture,” the world atlas was not “original in conception or execution” even at its release (ibid., viii and xiii). By 1676, the date recorded in the Francis Edwards catalogue, The Prospect was so obviously outdated that there was no further publication, and most of its plates—including the world map—were never reprinted (ibid.; Shirley 2004, 1:971). Yet because of the atlas’s relative scarcity except in Britain, original copies of the world map alone have gone for over $20,000 (Barry Lawrence Ruderman, email to author, July 18, 2014) rather than the £4 that Francis Edwards was asking in 1929.

A New and Accurat Map of the World epitomizes the baroque cartography that so enchanted Slessor: “If only world cd be like world of old mapmakers neatly parcelled into known and unknown” [sic], he declared on the seventh page of his Atlas drafts (March 5, -s64). Speed’s map continues to fascinate us today. Blame it on the map’s epic scope, its celebration of heroic adventurers, its ability to transport us—at a glance—across space and time. As Peter Whitfield says about a similar work copied from a 1629 world map, then printed in 1665 and republished in 1683 (Whitfield 1994, 92–93; see 96 for the “Pseudo-Blaeu World”):

It was from the 1580s onwards, the years also when the great Flemish mapmakers began to issue their newly-conceived world atlases, that the world map regained its encyclopedic, celebratory form. To this age heroic, classical imagery was a natural idiom for the new world map. But by the final quarter of the seventeenth century, the realities of trade and international rivalry, and the spirit of science, had made that idiom inauthentic and dated, and its appearance in this map is purely rhetorical.

Then too, whoever crafted the Speed world map lived in an age that still believed in mermaids. Henry Hudson sighted mermaids in 1608, as did Captain Sir Richard Whitbourne off Newfoundland; while Captain John Smith found them in the East Indies in 1614, and two men briefly captured a merman in 1619 after attending a Diet in Norway (Ellis 1996, 79–80; Benwell and Waugh 1965, 95–97). As the authors of Sea Enchantress: The Tale of the Mermaid and her Kin explain (Benwell and Waugh 1965, 86-87):

When renowned explorers and sailors such as Sir Walter Raleigh and Henry Hudson returned with reports of monsters and mermaids, who could doubt them? … What chance had intellectual doubts and skepticism against the stories of personal encounters with mermen and mermaid—some of them sworn to by persons of unimpeachable integrity?